8

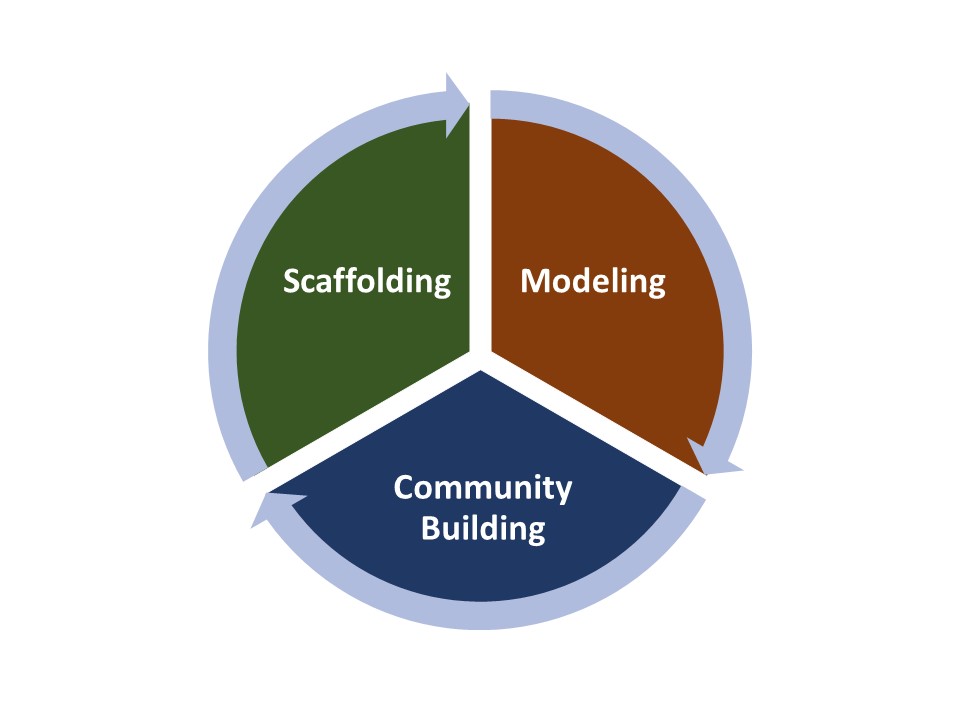

Aligning the major components of a course can be an important step towards preparing a meaningful learning experience for students. Another helpful step is to adopt a pedagogical strategy for structuring learning engagement in the class. Following the insights of Brookfield and associates (2019) concerning race-based teaching, the following three approaches – grounded in principles of inclusion and belonging, transparency, rigor, and collaboration – are one possible way of doing this:

Scaffolding: This entails an organized and often sequential process of onboarding students onto a rigorous path of inquiry. For example, rather than throwing students into the thicket of intersectionality theory before they reflect on how it might apply to themselves or a specific case study, an instructor might first have students reflect on their own social positions using an activity such as “I Am From…” (Klein 2019). This could be followed by engagement with case study of a first-hand account of someone who has been marginalized by an experience of intersectional power. Then students might be called to grapple critically with intersectional theory, for example the work of Kimberlé Crenshaw (1991) or Patricia Hill Collins (2019), or perhaps with a more accessible introduction such as the African American Policy Forum’s “A Primer on Intersectionality.” This in turn could inform a paper assignment in which students need to analyze and explain a particular case study through an intersectional framework, or they design their own primer on intersectionality for other students, or they prepare a group presentation. Finally, students could return again to self-reflection in a more critical way, examining their own experiences and identifications in more depth and articulating how their understanding of their relationships to power has changed as a result of their work. As this example illustrates, the idea of scaffolding is to begin where students are at, invite them into a structured process, and then support them in moving to more complex understanding (Brookfield 2019, 8). Adding a scaffolded process of emotional inquiry can amplify critical analysis, helping keep it productive. Instructors could, for example, have students early in a course reflect on their hopes and fears about engaging with difference and inequality, sharing their thoughts in small groups and generating combined class lists of hopes and fears that can be revisited throughout the term to see what has actually transpired or changed about their initial feelings. Or, an instructor could present a handout of common responses students experience when learning DIA material, such as those identified by Sue and Sue (1990, 112-117), and have students discuss strategies for how to work through such reactions. Students could then keep personal journals that chronicle their emotional reactions and intervention strategies, tracking what works and what doesn’t, as the class moves forward. Additional emotional support activities and strategies could be used (see Young and Davis-Russell 2014), but even the basic scaffolding described here can be quite helpful.

Scaffolding: This entails an organized and often sequential process of onboarding students onto a rigorous path of inquiry. For example, rather than throwing students into the thicket of intersectionality theory before they reflect on how it might apply to themselves or a specific case study, an instructor might first have students reflect on their own social positions using an activity such as “I Am From…” (Klein 2019). This could be followed by engagement with case study of a first-hand account of someone who has been marginalized by an experience of intersectional power. Then students might be called to grapple critically with intersectional theory, for example the work of Kimberlé Crenshaw (1991) or Patricia Hill Collins (2019), or perhaps with a more accessible introduction such as the African American Policy Forum’s “A Primer on Intersectionality.” This in turn could inform a paper assignment in which students need to analyze and explain a particular case study through an intersectional framework, or they design their own primer on intersectionality for other students, or they prepare a group presentation. Finally, students could return again to self-reflection in a more critical way, examining their own experiences and identifications in more depth and articulating how their understanding of their relationships to power has changed as a result of their work. As this example illustrates, the idea of scaffolding is to begin where students are at, invite them into a structured process, and then support them in moving to more complex understanding (Brookfield 2019, 8). Adding a scaffolded process of emotional inquiry can amplify critical analysis, helping keep it productive. Instructors could, for example, have students early in a course reflect on their hopes and fears about engaging with difference and inequality, sharing their thoughts in small groups and generating combined class lists of hopes and fears that can be revisited throughout the term to see what has actually transpired or changed about their initial feelings. Or, an instructor could present a handout of common responses students experience when learning DIA material, such as those identified by Sue and Sue (1990, 112-117), and have students discuss strategies for how to work through such reactions. Students could then keep personal journals that chronicle their emotional reactions and intervention strategies, tracking what works and what doesn’t, as the class moves forward. Additional emotional support activities and strategies could be used (see Young and Davis-Russell 2014), but even the basic scaffolding described here can be quite helpful.

Modeling: Nearly all approaches to anti-oppressive pedagogy emphasize the importance of instructor modeling. As bell hooks (1994) notes, “empowerment cannot happen if we refuse to be vulnerable while encouraging students to take risks” (1994, 21; see also Kishimoto 2018, 543). This is particularly the case for more vulnerable forms of inquiry such as self-reflection or emotional inquiry. In the example on intersectionality just described, an instructor would first demonstrate the “I Am From…” activity before having students do it, for instance. Modeling is also a powerful way to teach careful reading of texts or critical analysis of ideas, provided instructors clearly and explicitly indicate the moves they are making, for example demonstrating how to annotate a text “like an expert” or doing a “think aloud” to demonstrate basic questions they ask when thinking critically about an issue. In addition, modeling can include being explicit about how to engage in classroom discussion effectively, demonstrating the kinds of protocols and interactive moves that are effective indicators of ethically-motivated behavior; this can also include calling attention to and acknowledging when students make such moves, as examples for others to emulate. Of special significance in a DIA course, though, is instructor modeling of how we ourselves have come to awareness of power dynamics and the relationships between power and our own social positions and identities; how we navigate difference and inequality; and how this continues to be an ongoing process of learning, which includes making mistakes and learning from them, etc. along the way. This can include short explanations by instructors about our choices of texts or activities, or sharing appropriate anecdotes of particular situations we have experienced and how we responded. For white instructors, it can include explanation of how we have come to racial awareness of whiteness, our participation as beneficiaries of racist systems, and our strategies for intervening in them; for male-identified instructors, our awareness of and strategies for engaging gender dynamics or sexism; and so forth. In such cases, the point is to normalize DIA learning as a process, one involving vulnerability, courage, and growth, with each of us on a continuum, not at some final place of “arrival” (Yancy 2019, 19).[1] Modeling is a powerful and transparent way to demonstrate the core skills of DIA learning, and it helps establish and build trust with students.

Community Building: Students are more apt to engage in learning and collaborate with each other and instructors if they feel they belong to a learning community and have meaningful contributions to make. There are a variety of strategies for building community, including basics such as learning names, sharing goals and interests, and so forth. One approach that some UO instructors use involves “base groups” – having groups of two or three students meet at the beginning of class to check in with each other, share an interesting tidbit about their lives (based on a prompt provided by the instructor), discuss how prepared they feel for the day’s work, and so forth. Such low stakes interactions help build social connections and trust. The use of modeling also helps build community by opening a space for vulnerability, authentic sharing, and honest articulation of perspectives, ideas, feelings, etc., which will become important as the class progresses to more difficult material and issues. Instructors and students can also collaborate to construct a learning space that operates according to agreed norms, such as ground rules or guidelines for participation, plus specific protocols or strategies to take in certain situations. This can involve a brainstorming session in response to questions such as “How do we establish a class culture of participation that is welcoming to everyone, invites a wide range of appropriate contributions, allows for disagreement, and fosters respect for different perspectives?” “What are some reasons for why some students feel comfortable to participate, while others feel reluctant to do so?” “How can we respond to others respectfully when we disagree with them?” “How do we speak up if we notice a problematic dynamic of participation, such as certain students dominating the discussion?” “What should we do when our interactions get heated?” In some cases, instructors may want to stipulate important norms or protocols, have students practice using them, then debrief how it felt and what kinds of strategies may be needed to keep enacting the norms or practicing the protocols moving forward.[2] In any case, mutual collaboration in being vulnerable and in generating norms or protocols enables instructors and students to establish a “working alliance” together as a learning community (Cavalieri, French, and Renninger 2019). Similar community building exercises can be used to create a climate for critical inquiry and analysis. For instance, instructors can ask students questions such as “What is the goal of inquiry – to discover answers or fashion different questions or both?” “What kind of questions do you ask when you are truly interested in something?” “When do you truly know that some idea or perspective is right or wrong?” “What kinds of knowledge help us understand the experiences of others?” “If you didn’t have to worry about being right or appearing smart, what questions would you ask about this topic?” (Young and Davis-Russell 2014, 41-42). Exploring these questions can help introduce students to different ideas about what inquiry means and involves, and they can work together to craft a more complex approach to the work of critical analysis they will be undertaking in the class. Instructors can also assess the level of experience or facility that students have for inquiry and provide appropriate supportive materials. Such questions also provide students with initial practice in collective inquiry before they engage with more charged content.

Scaffolding, modeling, and community building can be used often, informing how instructors organize their daily class sessions or introduce students to activities and assignments. These approaches constitute a structure of support that can facilitate rich learning experiences.

- For examples of white instructors and scholars describing how they model racial awareness, see the essays in Yancy (2015a). Kendi (2019) provides an example of a Black male modeling awareness, and in his well-known letter, “Dear White America,” Yancy (2015b) models an approach to describing his sexism. ↵

- For example, one UO instructor introduces the following community norms for students to practice and keep practicing: 1. Stay engaged. (Listen deeply and ask with curiosity); 2. Speak what is true for you. (Beginning with I statements can be helpful); 3. Experience discomfort. (Reflections on your own discomfort are rich with new information); 4. Have an appreciative inquiry stance. (Assume good intent and be attentive to negative impacts); 5. Expect and accept non-closure. (Be open to unexcused outcomes as well as to ambiguity) ↵