Chapter 6 – Listening or Viewing Skills

Listening and Viewing Principles to Live By

Logan Fisher; Bibi Halima; and Keli Yerian

Taking in information and processing it can be daunting when learning a language! This is the case in interpretive mode when we are just listening to a video or a teacher in the class, as well as in interpersonal mode, when we are interacting with someone in real time. Often, we’ll only catch bits and pieces of what is being communicated (or nothing at all) and sometimes we struggle to follow the meaning. Although it can be frustrating, this is a normal part of the language learning process, but having the huge “aha” moment when things start to make sense makes it all worth it! So, what are some principles for listening (or viewing, if you are a signer) that can help us get there?

Find your comfort zone… then push a little beyond

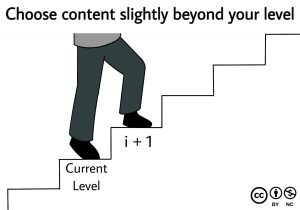

When listening or watching media on your own (such as watching TV or YouTube or listening to music), one of the most important principles is to choose content that’s at your level or a little beyond your level. There are more and more YouTube channels and podcasts to choose from that are designed to give real-life content to people who are learning languages. Pushing yourself to understand content slightly beyond what you already know will reinforce your current vocabulary and naturally teach you new material through inferences and context clues. Spend time in that “slightly beyond” zone until you realize you feel fully comfortable with the input you are getting. Then, it’s time to level up and be a little uncomfortable again.

Research Note

Krashen (1982) labels the situation of choosing content slightly beyond our current level as i+1. To break this down, i is defined as our current level of proficiency, and +1 means including some content a little above that level. Krashen posits that language acquisition happens best when learners process messages at their i+1 in their target language because they are able to process the meaning of the input relatively easily while getting exposure to a few new vocabulary, expressions, collocations, and structures in a meaningful context.

Be yourself and enjoy what you like

Choosing content that you enjoy for second language input can be really helpful in improving your receptive skills. If you like watching soccer, for example, try finding videos about it in the language you’re learning. If you have a favorite celebrity, try finding out what people in other countries are saying about them. Making language learning more enjoyable means that you’ll (likely) invest more into the process. You’re likely to want to keep learning since your motivation will be more intrinsic as we discussed in Chapter 1. When you like what you’re listening to or viewing, you are much more likely to get into a flow and enjoy it without getting frustrated. Who cares whether you’re learning language in a classroom or by watching trashy reality TV? The point is, you’re learning.

Research Note

According to Spratt et al. (2002), students who had more autonomy over their learning practices (in other words who chose their own content outside of class) showed more motivation and performed better in class. What content they chose to study, listen to or watch didn’t matter for their progress, just as long as they were interacting with the language! This shows that even if you are taking a language class with required content, you can still take responsibility for choosing your own content outside of class as well to keep your motivation high.

You don’t have to understand everything

Just as we talk about not worrying about speaking perfectly and focusing on communication instead of perfection, the same applies to your listening or viewing strategies. Typically when starting to learn a new language, we tend to focus carefully on each new element whether they are sounds, words, signs, or grammar (especially for languages far removed from the ones we know). When we start understanding at the level of phrases, sentences, and exchanges of language, we can start listening for the overall ‘gist’ of what we are hearing even if we don’t catch every word. If we don’t understand something, it’s best not to panic but to just keep listening since interpretation is never a precise science anyway. It’s all a part of the normal negotiation of meaning that we do even in our L1. Who knows, with this principle you could even learn language implicitly like you did in Chapter 2 with Faith teaching fruit words in Japanese.

Research Note

Students in an English class in Türkiye reported that after they started doing more extensive listening practice (listening at their level without stopping to look up words), they enjoyed listening more and even started dreaming in English, even if they didn’t understand all the vocabulary (note: these students were also choosing their own content to listen to!). Test scores also showed an increase in listening proficiency for most of the Turkish students (Turan Öztürk & Tekin, 2020).

The more the merrier

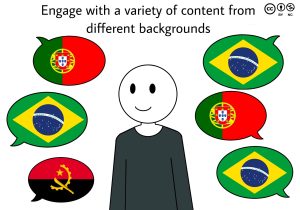

Engaging with diverse content by people of different backgrounds is another amazing way to develop not only your target language, but to understand the cultures behind the language as well. If you live in the United States surrounded by speakers from Latin America but you only learn the Spanish spoken in Spain, you will miss so much about the language and culture around you. On the other hand, if you never listen to someone from Spain before going there, you would likely have a much harder time understanding the locals. The same can be said for cultural exposure. The Arabic language and culture of someone from Egypt will be very different than those of someone from Saudi Arabia or Algeria. By widening your lens to listen to more than one community who shares a language, you are gaining a wider perspective of your target language and its culture(s).

Research Note

A study by Adams (2020) that illustrates this principle focuses on the listening abilities of missionaries from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints who recently returned from Spanish speaking countries. The participants were tested on their listening proficiency in different accents and were asked how many accents they had daily exposure to on their missions. The ones who had exposure to more diverse accents performed far better on the tests than those who had less.

Use the Technological tools available to you

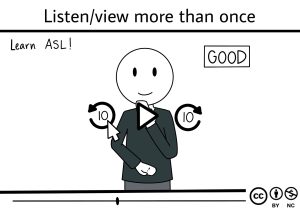

If you are interacting with content that isn’t in real time, such as videos, songs, or podcasts, you can rewind! The wonderful thing about technology is our ability to manipulate it to our liking, so if you didn’t catch something the first time, go back and try again. You can also slow down videos, as most programs now offer slower speeds. Granted, even when talking to someone in real time you can ask a person to repeat what they just said, but if you’re practicing on your own, you can go back as many times as you want. You can use this to aim for different goals. If you want to hear the language at its natural speed, then listen at normal speed, but if you are listening for details, slow down or rewind! You can do one of these choices first, and then the other, as a way to combine the two strategies. The more exposure, the better.

Research Note

Research Note

Chang et al. (2019) tested three groups on input comprehension. The groups were 1) listening only, 2) reading only, and 3) reading and listening plus a second listen. The post test showed that the third group improved the most and showed the best scores, averaging 84% compared to the 69% for the one-time listeners and 33% for the readers-only. This shows that not only is listening more than once very helpful, but also using multimodal input (Chapter 2).

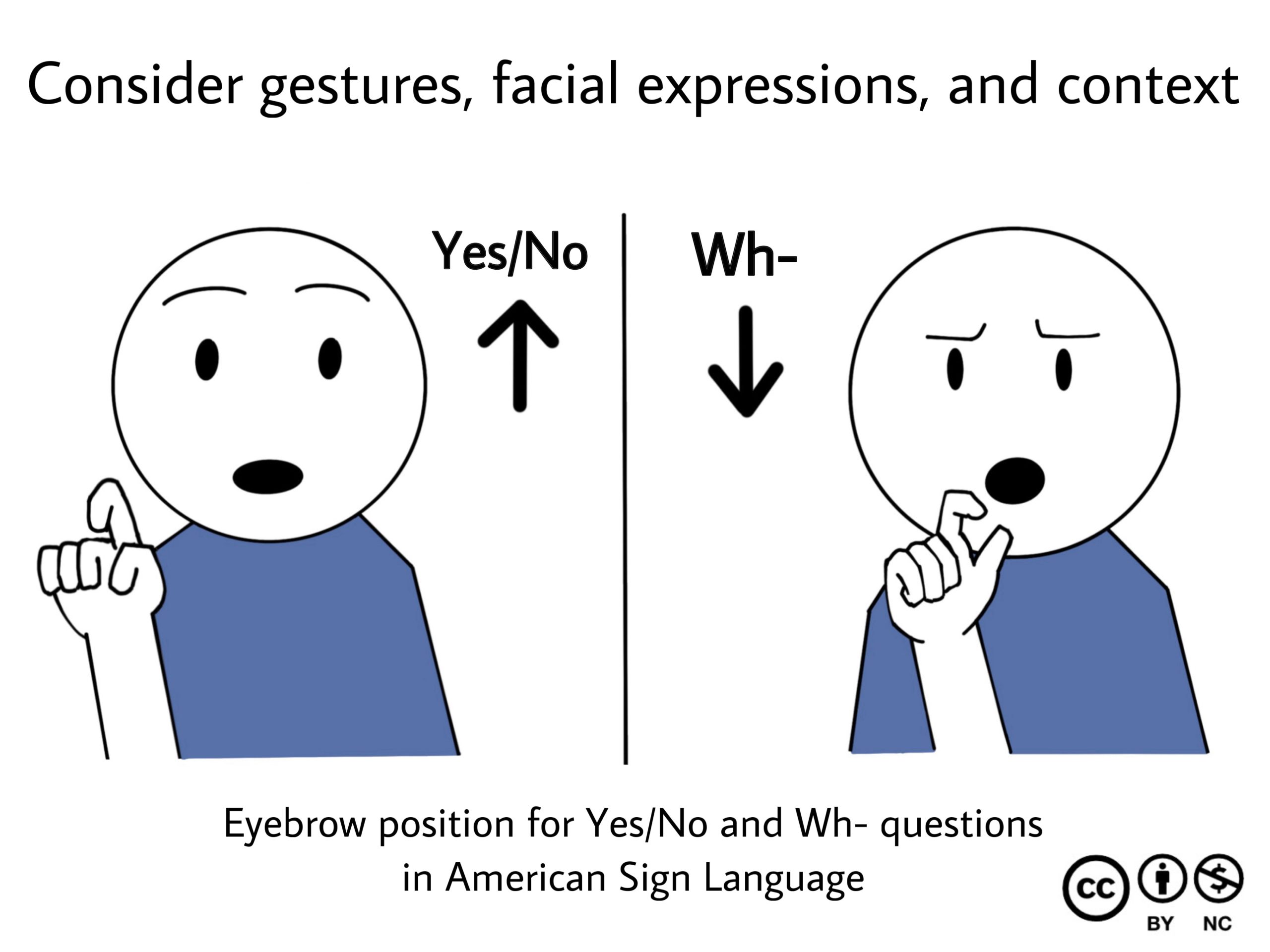

Find meaning beyond Words

Lastly, using context, multimodality like gesture and facial expressions, and any other forms of knowledge or props you can pull from is not a weakness, nor does it necessarily show a lack of ability or fluency in a language. It’s how we function as humans and how we learn! Think back to Chapter 2 when we talked about learning theories. Most things in life we learn by connecting patterns in our brains or by building knowledge with other people (Cognitivism and Constructivism). This can also happen with the use of translanguaging, especially if your conversation partner speaks two or more languages that you also speak. Think of listening to a conversation as a puzzle. You can use different knowledge and contexts to find the surrounding pieces of the puzzle and make that last piece fit in just right.

Research Note

In Sign languages, seeing the context of the whole body is important for interpreting the signs themselves. Slimane and Bouguessa (2021) created a computer model that is able to interpret Sign languages better than other models because it does more than perceive information from the hand, such as hand shape or movement. It also detects and analyzes information from the head and upper body.

References

Adams, N. T. (2020). Domestic vs. foreign immersion experiences: Listening comprehension of multiple dialects in Spanish [Masters Dissertation, Brigham Young University]. BYU ScholarsArchive. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/8724

Chang, A., Millett, S., & Renandya, W. A. (2019). Developing listening fluency through supported extensive listening practice. RELC Journal, 50(3), 422-438. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688217751468

Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Pergamon Press.

Slimane, F. B. & Bouguessa, M. (2020) Context matters: Self-attention for Sign language recognition, 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Milan, Italy, 2021, pp. 7884-7891. 10.1109/ICPR48806.2021.9412916

Spratt, M., Humphreys, G., & Chan, V. (2002). Autonomy and motivation: which comes first? Language Teaching Research, 6(3), 245-266. https://doi.org/10.1191/1362168802lr106oa

Turan Öztürk, D., & Tekin, S. (2020). Encouraging extensive listening in language learning. Language Teaching Research Quarterly, 14, 80-93. Find in Google Scholar

Media attributions

All original illustrations on this page © Addy Orsi are licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 (Attribution NonCommercial) license.

In this context, language that we are exposed to, e.g. through hearing, viewing (if signed languages) or reading

A noticeable arrangement or conjoining of linguistic elements (such as words). Ex: “Make the bed”, “To save time”

Any language learned after the first language(s). The term "second language" does not necessarily refer to the 2nd language in time that a person learns. It can be a third, fourth, or other additional language

Having the quality of receiving, taking in, or admitting. In the context of language, taking in input in the form of language

The overall idea of a spoken or written text. The “essence” of the text

A process of interaction in which speakers mutually negotiate their intended meaning using strategies such as clarification questions, repetition, and rephrasing to convey a clear message

The language learning technique of listening or reading extensive amounts of text to improve general comprehension. It is done without stopping to look up words or analyze the text

The language you are currently learning

The practice of mixing languages in a flexible way, either in speaking or writing