Chapter 9 – Writing Skills

Writing Principles to Live By

Faith Adler; Bibi Halima; and Keli Yerian

Though at first it can be intimidating to write in your L2, as well as find ways to do so intentionally, writing can be useful, motivating, and for some people, an indispensable part of a language learning toolkit. Even if in small ways, we write almost every day. Whether that be casual texting or formal emails, developing writing skills in one’s L2 can serve language learners in a variety of ways. And just as with all the other areas of language learning, as your writing skills improve so will the other areas. They all draw on one another for growth!

Let’s take a look at some core principles for writing in a second language.

Write to Communicate

What does it mean to write to communicate?

When you text a friend, do you use abbreviations, shortened phrases, or slang? Though these may not reflect “standard language”, this doesn’t matter. Your focus is on communicating a message.

Writing to communicate means using the vocabulary, grammar, and language skills that you already possess to share your thoughts or feelings. This means that while the writing might not always be “totally correct”, it can be understood by a reader even if it requires some interpretation and negotiation of meaning.

As we learned in Chapter 1, practice may not make perfect, but it will make proficient. Don’t be afraid to start simply and make mistakes as you learn to communicate your written ideas and feelings in another language.

Research Note

Park’s (2022) research showed that students who free-write or journal in their L2 are more likely to become faster at L2 writing and increase their confidence over time. After free-writing for only 10 sessions, students reported a decrease in writing anxiety, and they were able to express themselves more proficiently in their L2. Not only this, but their progress that was measured quantitatively (by calculating written words per minute) also improved over time.

Keep genre and audience expectations in mind

Do you use the same wording when texting a friend as when writing an essay? How about when writing a chemistry report versus writing a poem? Perhaps some of you would answer “yes!” confidently, but we’re guessing in most cases the answer would be no…

When writing, we should consider various factors such as audience, purpose, topic, and more. For example, you likely wouldn’t use the same language when posting on a casual online forum as when you’re writing an essay-style response to a test question. Keeping these factors in mind can help you to determine level of formality, word choice, and other stylistic factors. Distinguishing between styles of writing that are typical for different genres will improve your clarity of writing and ability to express your thoughts and feelings to your intended audience in your L2. When you pay attention to differences in genre in your target language, your writing can more closely approximate the expectations of readers in that culture.

Research Note

Ahn’s (2012) research showed that focusing on genre across 20 writing opportunities allowed students to recognize patterns in different L2 genres of writing. The students learned about genre expectations of their L2 (as they may vary from one’s L1!) and wrote within genre for the language. As they practiced on their own, they could make informed choices on when to adopt or not adopt certain patterns based on their own experiences and the voice they wanted to project within the genre.

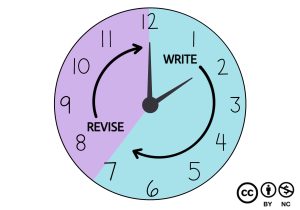

Build in Time for Revision

Though language can be thought of as first and foremost a tool to communicate meaning, this idea doesn’t take away from the importance of leaving ample time to revise when you want or need to, especially for writing. Finding just the right word to express your meaning, or checking carefully for grammatical errors, for example, is a way to build accuracy in your target language. In fact, revising for accuracy, even in text messages, can be of equal importance to communicating for overall meaning. Depending on who we are writing to, or how important the written text is, we may focus on accuracy to varying levels (remember our discussion in Chapter 4 about pragmatics). Giving attention to both writing to communicate and building time for revision helps us to become well-rounded writers.

Research Note

Your ability to communicate in your L2 writing may sometimes be hindered by a lack of grammatical or other practical skills and knowledge. Coomber’s (2016) research shows that students who invested in building self-correcting skills in their language learning journey experienced a variety of benefits. They were not only able to self-correct more effectively over time, but also noted feeling more confident about their ability to self-correct and the quality of their writing overall.

Use Technology to Support your Learning

Closely tied with the previous point, when you believe you have reviewed your work and made changes to the best of your ability, don’t be afraid to utilize outside sources and editing tools (such as Grammarly and Copilot) to improve your writing even more. However, this is not the only way to utilize technology in language learning. Apps such as HelloTalk and Slowly allow you to connect in writing with other speakers of your L2 (native and non-native). This can be an excellent opportunity to practice casual writing or ask questions about cultural norms that lie below the surface of the iceberg that you may not be able to find the answers to otherwise.

Recently, the emergence of generative Artificial Intelligence has given a tremendous boost to digital tools, including those for language learning. AI can be an incredible tool for supporting your writing, for example. It can generate ideas, analyze your drafts, and offer alternative grammar and vocabulary suggestions. But like any powerful tool, it can be misused as well, and even undermine your own learning if you use it to avoid the productive struggle of writing by asking it to do the writing for you. We encourage you to treat AI as a tool to improve your own thinking, not as a replacement for it.

Research Note

Students who use technology both inside and outside of the language learning classroom tend to show increased learner achievement and enthusiasm about its use (Diallo, 2014 ). Enayati and Gilakjani (2020), for example, show that over the course of just 12 sessions of practice with a software that provided personalized interactive vocabulary tutoring, students were able to increase their vocabulary size at a higher rate than students who studied the same vocabulary using more traditional methods. The benefits of using technology for individualized learning pathways produced better results.

Allow Your Voice and Style to Grow

It’s only natural that you will not be able to fully express yourself in your L2 writing, especially in the beginning. This likely happens in your L1 sometimes, too! However, as you go through this struggle, negotiating meaning with yourself and others, you will slowly develop a unique voice in your L2. Our unique voices, or individual styles of personal expression, can indirectly communicate about who we are without us directly explaining our identities or histories.

Just as there will be times when you must clarify and negotiate your meaning, there will be other times where you write something that those around you find quite profound without any need for negotiation. You might even be surprised by what comes out when you allow yourself to write freely. As we explored earlier in Chapter 4, learning new languages and cultures can have a significant impact on our perception of the world and expression of ourselves as we navigate exchanging meaning with others. Learning a new language can support our creativity as we explore new ways to express ourselves.

Research Note

Kubokawa’s (2022) research shows that when students were supported in developing voice in their L2 through poetry, students felt a greater sense of agency and investment in their language studies. Through experimenting with both the norms and rules of their L2, students were able to develop a deeper understanding of their L2 as well as themselves in relation to that language and culture.

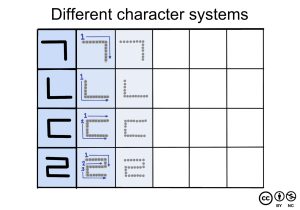

Writing Across Different Character Systems

Different character writing systems are used by languages all around the world. While some may have small differences from your L1, such as different pronunciations of letters or the use of accents in the alphabets (such as how Spanish uses written accents on words but English doesn’t), others might have dramatically different writing systems, such as the differences between Arabic and Spanish. A new script system can feel like an intimidating wall to climb when we are considering learning a new language. However, it certainly shouldn’t be something that we let get between us and learning a language we are passionate about.

When learning a new writing system, it is constructive to consider what is the same about the new system compared to your L1, as well as what is different. This allows us to make easy connections with what we already might know, as well as notice unfamiliar elements to focus our attention on. This might start from shared sentence structure, characters, grammatical features, or otherwise. Even when it seems there is no overlap between two writing systems, a few points of similarity can always be found, if only in small ways.

From here, we can utilize some learning strategies such as using mnemonics to assist us in learning new characters. However, it’s true that much of the work is going to be done through the use of rote memorization strategies and materials such as flashcards. In general, learning the system sooner than later and practicing the writing system as frequently as possible can help you move beyond the tedious memorization that must be done so you can start expressing your own meaning in new and creative ways.

Research Note

Qu et al. (2024) show that keyword mnemonics (one way of memorizing a second character system) can help support memory. When students were using rote memorization as opposed to mnemonics, they had a more difficult time reproducing learned characters. In contrast, when students took part in the highly creative process of coming up with mnemonics to learn new characters, they found more success in retrieving the information.

References

Ahn, H. (2012). Teaching writing skills based on a genre approach to L2 primary school students: An action research. English Language Teaching, 5(2), 2-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/elt.v5n2p2

Coomber, M. (2019). Self-directed revision in L2 writing classes at a Japanese university: A study of students’ views. TESL Reporter, 52(2), 42-72. https://esw.byuh.edu/00000174-7f9e-dd0c-a9fe-ff9f0aa40000/article-3-pdf

Diallo, A. (2014). The use of technology to enhance the learning experience of ESL students [Master’s dissertation, Concordia University, Portland]. Online Submission. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED545461

Enayati, F., & Gilakjani, A. P. (2020). The impact of computer assisted language learning (CALL) on improving intermediate EFL learners’ vocabulary learning. International Journal of Language Education, 4(1), 96-112. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1249911

Kubokawa, J. M. (2022). Effects of an L2 writing poetry pedagogy: Tracing learner development of authorial voice and agency. International Journal of TESOL Studies, 4(4), 40-62. https://doi.org/10.46451/ijts.2022.04.04

Park, J. (2022). Preservice teachers’ L2 writing anxiety and their perceived benefits of freewriting: A case study. English Teaching, 77(1), 63-77. https://doi.org/10.15858/engtea.77.s1.202209.63

Qu, K., Liu, T., Qiao, Y., & Wang, P. (2024). The facilitative effect of the keyword mnemonic on L2 vocabulary retrieval practice. Heliyon, 10(3), e25212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e25212

Media Attributions

All original illustrations on this page © Addy Orsi are licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 (Attribution NonCommercial) license.

Any language learned after the first language(s). The term "second language" does not necessarily refer to the 2nd language in time that a person learns. It can be a third, fourth, or other additional language

A language variety that is considered to be more 'correct' or 'proper' and thus has more power and importance in a community

A process of interaction in which speakers mutually negotiate their intended meaning using strategies such as clarification questions, repetition, and rephrasing to convey a clear message

Other factors related to the style of the writing such as tone, voice, unity, and coherence

A specific type of written or spoken text, such as novels, newspapers, blogs, speeches, conversations, etc

In the field of education, this term refers to the student's ability to actively participate in their own learning by making meaningful choices in selecting content or learning goals