Chapter 4 – Culture, Intercultural Competence, and Pragmatics

Going on a Culture Expedition

Faith Adler; Bibi Halima; and Keli Yerian

Preview Questions

- How can we conceptualize the complexity of culture?

- What are some models for understanding the experience of culture shock?

What are some of the language features that come to mind when you think of a language classroom? Grammar? Vocabulary? Have you ever considered that learning about culture could be just as important as these other components of language? Cultures (and sub-cultures) can shape how people speak to and interact with one another. In this section, we will take a look at a few ways to conceptualize culture.

Culture as an Iceberg

You might be familiar with how we perceive icebergs. Though we can see the surface, this only captures about 10% of what is there. Similarly, culture can be seen as an iceberg. There are parts of cultures that are easy to see and are talked about often such as language, art, food, or fashion. However, these topics are only the visible surfaces of culture, as we can see in the illustration below.

There are also subjects that are talked about less frequently, such as how to behave in business settings, or the symbolism of certain gestures. These patterns are just part of everyday life, and usually remain just below the surface.

Then, there are subjects and behaviors discussed even less frequently. These are so deeply embedded in those who grew up in the culture that they occur as thoughtlessly as breathing. This might include norms between genders or ages, how the culture values personal space, or even what is seen as “good” or “bad.” These aspects remain deeply hidden unless we are willing to acknowledge and discuss them.

Being aware that a culture we are interacting with may have some norms that are below the surface reminds us to keep our eyes, ears, and minds open. It allows us to dive deeper into an unfamiliar culture and get to know the people behind it in a respectful manner as well.

ROTEX Perspective: Common Misconceptions

Another shared experience we all had studying abroad was how much we were stereotyped by others. We were always happy that people felt comfortable enough to ask about culture in the United States, but it would almost always be about the stuff you see in the movies. “Do you guys really party all the time?” or “Do people really get shoved in lockers?” were a few examples. They might seem silly to us – but those are the sort of things that sit right at the surface of culture, so of course people who aren’t familiar with culture in the United States are going to ask about them.

Eric brought up how sometimes people think that they have a strong knowledge of a culture (or are more knowledgeable than others in their circle) even if they’ve only had minimal exposure, but in reality, it’s really difficult to know and understand a culture if you’re not actively involving yourself in it. He said that “Culture is not visible if you are not immersing yourself in that culture.”

Don’t Let Culture Shock Surprise you!

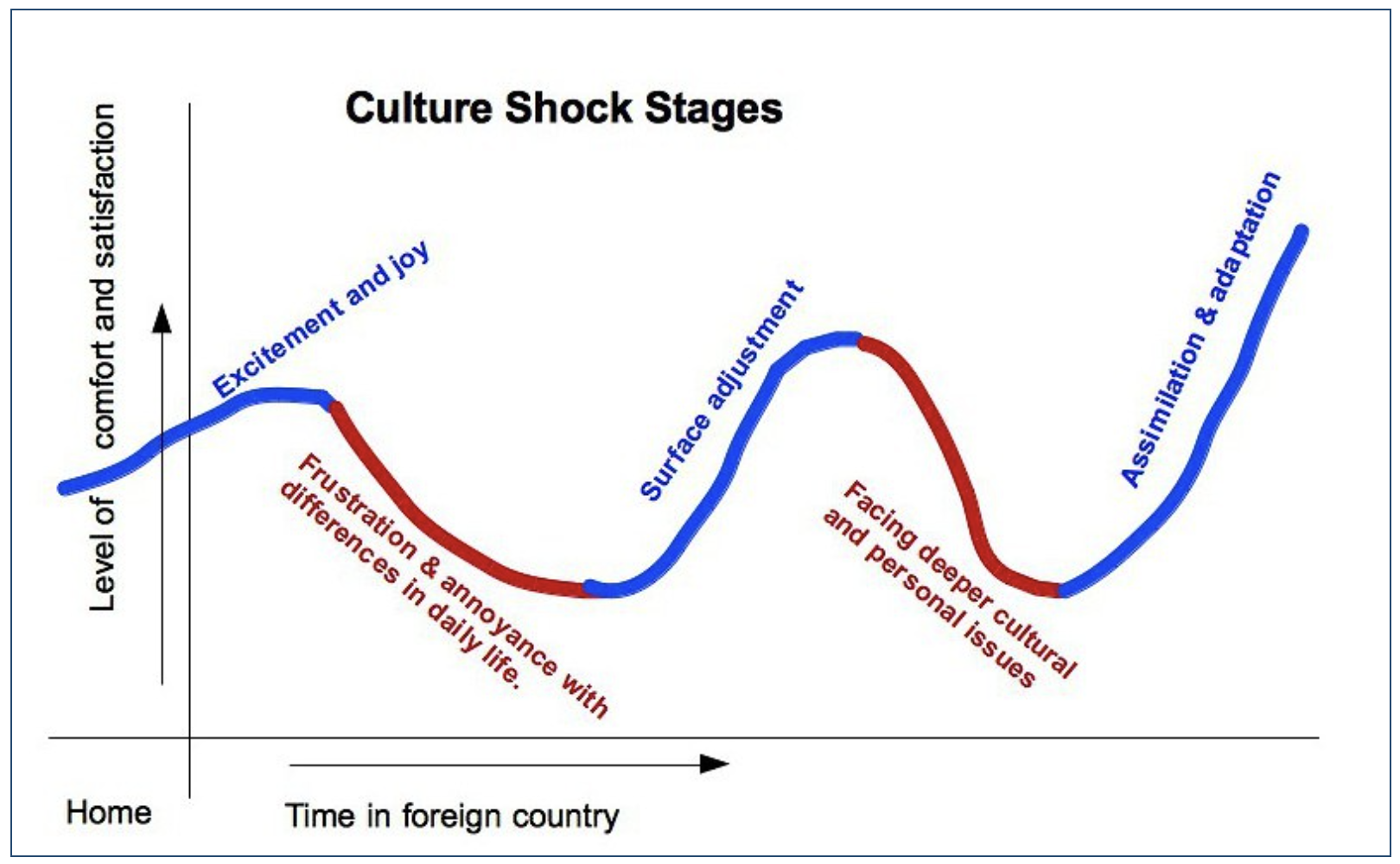

When we begin to explore a new culture or sub-culture, and especially as we start to get lower in the iceberg, we can experience something called culture shock. This experience isn’t a linear process and can feel a bit like a roller coaster, as represented in the illustration below. We often experience excitement and joy early in our journey, but then can become irritated and frustrated at the differences that start becoming visible to us. Over time we might adjust to the surface differences, but still encounter deeper cultural and personal challenges before eventually assimilating and adapting. Many people may never fully adapt, depending on their personal values and choices.

Culture shock can be big or small. Sometimes you’ll learn something new about a culture that changes your entire perspective, and sometimes you’ll learn something new that might be just a bit of an inconvenience to get used to. You can even experience culture shock across sub-cultures. There will be times when you like what you learn, and there will be times when you don’t like what you learn. All of these are normal and valid feelings when encountering a new culture, so feel free to embrace those feelings as they come and go.

ROTEX Perspective: Education

One thing that we found in common among Japanese, Thai, and Turkish cultures was the value placed on formal education. In all three countries, students would have to apply and test into their high schools. Many students wouldn’t engage in much social activity outside of class because they felt that they needed to prioritize studying over their social life. Eric mentioned that he often wondered about what kind of impact the Thai education system had on students beyond just the surface. Formal education being prioritized at the level it was in our respective host countries was an experience of culture shock.

If you’d like to read more about culture shock, this OER by Grothe (2021) can be a useful place to start.

Like the culture shock stages shown above, the Intercultural Development Continuum (IDC) is another model that visualizes the developmental stages we may go through when deeply learning another culture. The IDC model describes five orientations towards cultural differences that include denial, polarization, minimization, acceptance and adaptation that we may experience as part of culture shock. Please follow this link to learn about and interact with the IDC. In the interactive visual below, Faith explains how she applies the IDC model to her own experience with cultural expectations about cell phone use in schools in Japan. Follow along with Faith’s evolution through the various stages of the continuum.

Author’s Perspective – Faith

When I studied abroad in Japan, one example of culture shock I had was how strictly rules were enforced and adhered to. In most schools across Japan, you are generally not allowed to use phones on campus, even when classes are not in session.

As you read Faith’s story, try to think if you have a similar experience in another cultural or sub-cultural context. Can you identify which IDC orientations you had in that situation? Did your orientations change?

As we reach the end of this section, do you remember the “culture as an iceberg” we took a look at above? Try to place some of these cultural values and behaviors on the iceberg in terms of how “close to the surface” they are.

Culture as an Iceberg Comprehension Check

Drag the key terms from either side and drop them onto the iceberg at their correct positions, either above the surface or below the surface.

References

Grothe, T. (2023). Exploring intercultural communication. LibreTexts Social Sciences. https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Courses/Butte_College/Exploring_Intercultural_Communication_(Grothe)/06%3A_Culture_Shock/6.01%3A_Introduction_to_Culture_Shock.

Media Attributions

All original illustrations on this page © Addy Orsi are licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 (Attribution NonCommercial) license.

Culture Shock stages © Vera Loen is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license.

Image Description

Figure 1

An Iceberg with visible parts of culture above the surface of the water:

- Language

- Literature

- Art

- Dress

- Religion

- Food

Hidden aspects of culture are below the surface:

- Beliefs and values

- Marriage

- Personal space

- Gender roles

- Non-verbal communication

- Eye contact

- Body language

- Power dynamic

- Modesty

- Attitude to elderly

- Tone of voice

- Obscenities

- Sense of “self”

Media Attributions

- culture-shock-stages

Groups that are part of the dominant culture but that differ from it in important ways

Both positive and negative feelings associated with adjusting to a new culture