Chapter 1 – The Secrets of Language Learning

Language Ideologies and Language Learning Myths

Bibi Halima and Keli Yerian

Preview Questions

- What are language ideologies and why do they matter?

- What are some common language learning myths?

Nod and smile if you’ve assumed any of the following to be true:

- Some languages are inherently more difficult than others.

- Some languages are inherently more logical and beautiful than others.

- Some languages sound funnier than others.

- There is always a proper way of articulating a word in a language.

- The best kind of language is produced by native speakers.

- The best way to learn a language is through immersion or study abroad.

Keep smiling and read on.

These assumptions are a few of the widely held beliefs about language learning. In the last section you learned that you don’t need to share a language to communicate with someone, much less know it perfectly. But maybe you still think that you need at least a year or two in a language class before you begin trying to speak. Perhaps you think you’ll never be able to speak like a native, so you are discouraged to try. These beliefs are the examples of language ideologies.

language Ideologies

Michael Silverstein, one of the leading figures in linguistic anthropology, defined these ideologies as “sets of beliefs about language articulated by users as a rationalization or justification of perceived language structure and use” (Silverstein, 1979, p. 193). Interestingly, these ideologies are ubiquitous but they do not come from human reasoning. Instead, they show us how people feel about and perceive a particular language or languages in general.

Do Language Ideologies Matter?

Imagine a scenario where a job applicant is judged negatively in an interview based on their regional dialect, despite being highly qualified. This implies that the interviewer holds a standard-language ideologyand we can infer that the interviewee’s dialect is considered less prestigious and professional.

To know more about the case of Pakistan, read an opinion by Punjani and Khan (2020).

It is important to note that language ideologies do not always have negative impacts. If they are constructive and progressive beliefs about language diversity, these ideologies can bring a massive change in making the world more tolerant and diverse for all. Language ideologies are game changers! To visualize and understand the power of a language ideology that believes in preserving endangered and local languages, look at the example of UNESCO’s project in the Amazon region of South America, which focuses on safeguarding linguistic and cultural heritage.

You might realize at this point that we too (as authors) have a language ideology in this book. Our ideology promotes the message that every language matters. For example, that efforts should be made to preserve endangered languages. To answer the question ‘does language ideology matter?’ we should understand that these beliefs about language shape our identities and drive the course of social actions as well. Think about it – the way we perceive and talk about languages influences everything, from how we make friends to how we judge others in job interviews. It also influences how we learn new languages.

Language Learning Myths: Questioning the Obvious

Language ideologies are everywhere and we want you to notice that they contribute to your own language learning process as well. For example, if you think Hebrew is too complex of a language to learn, you will probably not choose to learn it. And if you subscribe to the idea that language learning in general is difficult, you may not even start to learn at all. This TedTalk by Mathew Youlden explains that learning any language can be an easy task if one starts the journey with questioning their own myths.

Since this is the first chapter of this book, let’s take the opportunity to debunk some obvious myths about language learning right from the beginning. For example, in the last section we saw that we can communicate even when we feel that we do not know a language well enough to do so. The idea that communication is limited to language is one of the common myths. Let’s explore what some of the other ones are.

Myth 1: You can only learn languages easily when you are young. I’m too old now!

If someone says any of the following:

- Babies learn faster than adults.

- Learning a language is easier for children.

- The best time to learn a language is in one’s initial years of life.

They are referring to the critical period hypothesis . There is a big discussion in the subfield of Linguistics called Second Language Acquisition (SLA) about how age plays an important role in learning languages. But what exactly the role is remains a debate among scholars. Penfield and Roberts (1959) first proposed the hypothesis that our ability to learn languages gets diminished after a biologically determined phase. The hypothesis promotes the notion that the sooner a child starts learning a language the better.

. There is a big discussion in the subfield of Linguistics called Second Language Acquisition (SLA) about how age plays an important role in learning languages. But what exactly the role is remains a debate among scholars. Penfield and Roberts (1959) first proposed the hypothesis that our ability to learn languages gets diminished after a biologically determined phase. The hypothesis promotes the notion that the sooner a child starts learning a language the better.

However, this remains only a hypothesis to this day!

Yes, it’s true that children tend to learn seemingly effortlessly in their naturalistic and immersive environments, unlike adults who tend to put themselves in a conscious state of mind to learn a language. But many adults learn languages very well! It is never too late to learn a language, even fluently. Claiming that it is ‘easy’ for children to learn a language is debatable. Even with constant immersion and simplified motherese, it takes babies many months to say their first word and children take several years to develop their first language completely. Let’s say 4-6 years! And they continue to become more sophisticated across more topics and domains as they mature into adulthood.

Yes, it’s true that children tend to learn seemingly effortlessly in their naturalistic and immersive environments, unlike adults who tend to put themselves in a conscious state of mind to learn a language. But many adults learn languages very well! It is never too late to learn a language, even fluently. Claiming that it is ‘easy’ for children to learn a language is debatable. Even with constant immersion and simplified motherese, it takes babies many months to say their first word and children take several years to develop their first language completely. Let’s say 4-6 years! And they continue to become more sophisticated across more topics and domains as they mature into adulthood.

So can we say it’s really that easy for children? It is not a one-night transformation for adults either. Language learning can take a lot of time and that’s okay. Adults have the advantages of being able to consciously dedicate themselves to the task, to be more cognitively mature, and to already speak at least one language. In short, it is completely possible to learn a language at any age you wish to do so. If you want to know more about this topic, listen to Kaitlyn Tagarelli on Am I too old to learn a new language?

Myth 2: You can learn a language, but only if you have language in your DNA.

Maybe you have heard some people saying one or more of the following:

- Some people are better at languages than others.

- Languages come so naturally to that person.

- I have a gift for languages.

It is true that some people exhibit remarkable progress when learning language, but does it mean that some people have language in their DNA? No, it does not. Instead, it is about language learning aptitude and the motivation people have towards a language. Language learning aptitude is a prediction of how well you can learn the different skills of a language. For example, some learners can differentiate subtle sound differences and reproduce them very well. This may be because of their previous language learning experiences or simply their ability to distinguish sounds. This does not mean they have innate language learning abilities.

Someone who has the ability to differentiate sounds may be able to learn tonal languages like Chinese or Vietnamese more quickly than those who struggle to discern sounds. Language learning aptitude is usually predicted by a formal aptitude assessment like The Modern Language Aptitude Test (MLAT). It is important to note that this aptitude is not fixed, innate or static for all languages. It can change for different languages and one can improve it during one’s language learning journey (Singleton, 2017).

Someone who has the ability to differentiate sounds may be able to learn tonal languages like Chinese or Vietnamese more quickly than those who struggle to discern sounds. Language learning aptitude is usually predicted by a formal aptitude assessment like The Modern Language Aptitude Test (MLAT). It is important to note that this aptitude is not fixed, innate or static for all languages. It can change for different languages and one can improve it during one’s language learning journey (Singleton, 2017).

More than aptitude, motivation plays a key role. If you have a strong desire to learn, you’ll learn faster than someone who simply has more aptitude, just like learning any other skill such as cycling, knitting, or baking. Imagine you are traveling to a different country in a month and you are motivated to learn some basic expressions in order to communicate with people. This upcoming trip will likely motivate you to make more consistent efforts to learn the language than if you were not traveling. Despite individual differences in aptitude, your motivation will make the most difference. If you want to know more about this topic, listen again to Kaitlyn Tagarelli on Are some people just good at learning new languages?

Myth 3: All you need is… Grammar and Vocabulary

[Loud beep sound please] This is a BIG myth!

It is true that both grammar and vocabulary are essential parts of language but they are far from being everything. Imagine you want to learn how to drive but you focus only on learning the different parts of the car. Would that be enough? Of course you need to know what the engine and brakes are but what matters the most for drivers is whether you can hit the brake when the traffic light turns red. Similarly, while grammar and vocabulary are the ABCs of language, you still need creative, interactive practice to learn to communicate in it.

Unfortunately, most language learning settings stress the ABCs and this kind of explicit learning can support the ideology of prescriptivism, which tells us the ‘correct’ and ‘incorrect’ use of language and emphasizes strictly following standardized rules. This ‘should-do’ and ‘must-do’ ideology can demotivate learners and prevent them from jumping into communication. Remember that language is a social activity; while it is fine to start with some ‘should-dos’ (some basics ‘rules’ of the language), it is equally important to discover some ‘could-dos’ (creative possibilities for using the language). And it is always important to remember the primary purpose of language learning is communication.

Myth 4: Choose one or the other! Languages must be pure!

Imagine Maria is learning Spanish in the US. It is her first year of learning and she has developed remarkable conversational fluency. Her first language is English and when she talks to her friends who either know or are learning Spanish with her, her conversations look like this…

Maria: ¿Hola, que tal?

Anthony: Hey Maria, I’m alright, but life’s been busy lately. ¿Y tu?

Maria: Vale, a veces work can be really stressful.

Anthony: For sure, and you know the deadline for the final project is coming up.

Maria: Oh, don’t remind me. El trabajo nunca se acaba.

Notice how seamlessly Maria and Anthony mix the two languages in the example above. This process of mixing languages is called translanguaging. This is a theoretical lens that views languages as dynamic, flexible, and fluid systems for communication. Although we label languages as ‘Spanish’, ‘English’, ‘Arabic’, ‘French’, etc., research indicates that the bilingual or multilingual brain does not store languages as different systems. As Vogel and Garcia (2017) explain “… there are not two interdependent language systems that bilinguals shuttle between, but rather one semiotic system integrating various lexical, morphological, and grammatical linguistic features in addition to social practices and features…” (p. 5).

If you are hearing the idea that languages are not actually separate systems for the first time, you must be wondering, “Is that really true?” and your brain might trick you here with the ideology of linguistic purism. It’s also possible you feel pressured to keep your target language free from the influence of your first language. But rest assured that blending two or more languages is a normal human activity for multilinguals. In other words, you don’t have to choose only one language to speak at a time… unless you choose to! If you want to know more about translanguaging as it can be used in language classrooms, listen to Eowyn Crisfield, What is translanguaging, really?

If you are hearing the idea that languages are not actually separate systems for the first time, you must be wondering, “Is that really true?” and your brain might trick you here with the ideology of linguistic purism. It’s also possible you feel pressured to keep your target language free from the influence of your first language. But rest assured that blending two or more languages is a normal human activity for multilinguals. In other words, you don’t have to choose only one language to speak at a time… unless you choose to! If you want to know more about translanguaging as it can be used in language classrooms, listen to Eowyn Crisfield, What is translanguaging, really?

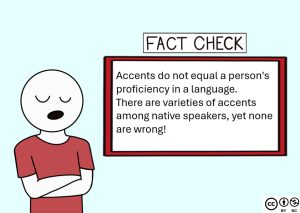

Myth 5: I need to sound like a native speaker

“Do you know what a foreign accent is? It’s a sign of bravery!” – Amy Chua

We have heard so many times fellow students in language classes say things like “I don’t want to be disrespectful” or “I don’t want to sound dumb” when it comes to pronouncing words in other languages. But think about it, we all have an accent, even in our native languages. In the Pacific Northwest of the United States we have a different accent in English than people from the East coast, the South, or the Midwestern United States. And it’s certainly different from the accents of people from New Zealand, Scotland, or India. You probably wouldn’t think to correct the way a Canadian says “about” or the way an Australian says “under” because you know it’s just the way people from those places speak, it’s just their normal accent. So why when a Spanish speaker speaks English with a “Spanish” accent does it suddenly become a problem? Why is the solution to this “problem” always to correct the accent? Oregonians don’t correct Canadians or people from the East Coast, so why are certain types of accents okay and not others?

The idea of “proper” pronunciation comes from an ideology called nativespeakerism, another one of those things that exists due to power, i.e. the prestige of a native speaker over a non-native one. This term was coined by Holliday (2005) with regards to English language learning and English language teaching. However, it is not restricted to any one language. Many speakers of other languages also assume that native speakers are always better speakers than those who have learned languages later in life.

Now ask yourself, where did you learn how to pronounce things in your second language? Your language teacher? Social media? Your parents? Where do you think your parents or language teacher learned that pronunciation from? Probably from their parents or language teachers. And the further back you go you realize that “proper” pronunciation is just whichever pronunciation was most used or accepted at a given time by the people who were called “native” speakers of a particular language.

This is a damaging belief. If you restrict yourself to this discriminatory language ideology, be aware that you are limiting your chances for growth and the endless possibilities in language learning. Every accent is unique and beautiful; your efforts do not deserve biases and prejudice from yourself or from others. Your efforts instead are a sign that you are courageous and resilient enough to step out and embrace a bilingual journey.

Now that you have reached the end of this section, how would you respond to the following statements?

Language Myths Comprehension Check

Select the best answer for each question.

References

Holliday, A. (2005). The struggle to teach English as an international language. Oxford University Press.

Penfield, W., & Roberts, L. (1959). Speech and brain-mechanisms. Princeton Legacy Library.

Silverstein, M. (1979). Language structure and linguistic ideology. In P. R. Clyne, W. F. Hanks, & C. L. Hofbauer (Eds.), The elements: A parasession on linguistic units and levels (pp. 193–248). Chicago Linguistic Society.

Singleton, D. (2017). Language aptitude: Desirable trait or acquirable attribute?. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 7(1), 89-103. http://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2017.7.1.5

Vogel, S. & Garcia, O. (2017). Translanguaging. In G. Noblit, & L. Moll (Eds.), Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.181

Media Attribution

All original illustrations on this page © Addy Orsi are licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 (Attribution NonCommercial) license.

A set of shared beliefs and feelings about language that connects language and society

A variation of a language specific to a certain geographical location or region

"A bias toward an abstract, idealized homogenous language, which is imposed and maintained by dominant institutions" (Lippi-Green, 1997).

Having a high level of regard. Within sociolinguistics, a prestigious language variety is one that is considered more "correct" by those in power and society

Languages in danger of losing all speakers and disappearing

Languages specific to local people of a particular community, region, or social group

According to this hypothesis, age plays a critical role in acquiring a native-like proficiency for any language. It claims that there is a limited time frame in which to learn languages well that spans from early childhood to adolescence

A specific way of talking to infants or young children, also commonly known as baby talk

Different contexts of language use, such as home, school, or work

A prediction of an individual's ability to learn a foreign language, compared to others, within a specific timeframe and under particular conditions

Reasons and objectives that inspire people to learn a new language(s). It can be intrinsic motivation that comes from within and linked to personal fulfillment. It can also be extrinsic that is influenced by external factors such as learning a language as an academic requirement to complete a degree program

A strict adherence to established language rules and norms, considering deviations from the standard form as incorrect or improper

The practice of mixing languages in a flexible way, either in speaking or writing

Related to Standard-Language Ideology, this is the prescriptive practice of describing one language variety as being the most "correct" or most "pure", and therefore of higher value than other varieties

An ideology that native speakers are better speakers and have the more 'authentic' knowledge of the target language(s) than those who have learned the language(s) later in life