Chapter 2 – Approaches to (Language) Learning

Procedural and Declarative Knowledge

Logan Fisher; Bibi Halima; and Keli Yerian

Preview Questions

- What is the difference between procedural and declarative knowledge?

- What are examples of procedural and declarative knowledge?

- How does this relate to language learning specifically?

An important part of language learning is gaining and processing information or in other words, knowledge! While there are many classifications of knowledge you can see in literature, two types of knowledge play a crucial role in language learning: procedural and declarative. This section not only differentiates between the two with examples but also extends them to language learning to explain how they work together. As you navigate the discussion and activities on this page, be sure to notice that building both of them are essential for your effective language learning.

Procedural knowledge

Do you have your driver’s license? Maybe you ride your bike to work or to school. Or maybe you just walk. In any of these cases, if it is a routine, you probably do these actions without thinking about the specific procedures of how to get to your destination. For example, the daily ritual of how to start your car becomes automated. Similarly, if you bike, you most likely don’t think about the mechanics of biking or even the speed you’re going for the most part. It becomes what we call procedural knowledge, or “knowing how to do something” (Carpenter et al., 2000, p. 7). The focus here is on the ‘how to do’ part.

To extend this analogy to language learning, think about how you speak in your first language(s). You are able to use it effortlessly without thinking about its grammar patterns, for example. You can also build procedural knowledge in your second languages when you internalize its patterns. This is like driving a car without the need to think consciously about the parts of the car or how to operate them.

Declarative knowledge

Declarative knowledge is another way of knowing. It is defined as, “knowing about something… the ability to discuss, explain, and analyze something” (Carpenter et al., 2000, p. 7). The focus here is on the ‘about’ part. Now we’ll ask you the same question that we asked earlier. Do you have your driver’s license? If yes, and you live in the United States, you had to take a online test inside the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) to demonstrate your conscious knowledge of traffic laws and parts of the car.

In the context of language learning, when we are able to consciously identify verb conjugations and figure out which pronoun to use for certain objects in gender-based languages, for example, it is like taking a test on the DMV computer to demonstrate what you know about the parts of the vehicle and their functions.

Putting the two together

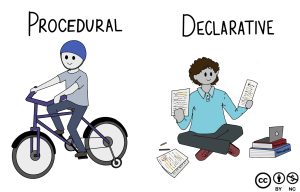

To continue this driving test analogy, taking the road test to demonstrate your ability to actually drive is like conjugating past tense in a target language conversation without having to even think about it! It is second nature and comes naturally without thought. That’s what the road test is testing for! The DMV wants to be reassured that these skills are automated for every driver on the road. Similarly, once we’ve learned to ride a bike, we no longer have to spend explicit mental energy to remember how to pedal or steer. As shown in the illustration below, procedural knowledge is knowledge demonstrated through action (that you may not know how to explain) whereas declarative knowledge is knowledge that you can easily explain.

When you are getting familiar with these two aspects of knowledge, do not jump to the conclusion that these are two separate “about” and “how to do” storage boxes in your brain that never interact with each other. There is some debate among second language research scholars about whether and how these two are related in our minds. Some scholars say that procedural knowledge must develop on its own subconsciously, parallel to declarative knowledge, while others say that declarative knowledge can become procedural knowledge through practice. Lightbown and Spada (2013) review this position as stating:

“most learning, including language learning, starts with declarative knowledge, that is, knowledge that we are aware of having, for example, a grammar rule. The hypothesis is that, through practice, declarative knowledge may become procedural knowledge, or the ability to use the knowledge. With continued practice, the procedural knowledge can become automatized and the learner may forget having learned it first as declarative knowledge” (p. 109).

This position claims that, especially for adult language learners, much of what we know about a language is first declarative, and procedural ability develops with extensive practice and exposure. However, whether or not exposure and practice allows procedural knowledge to develop separately or whether it develops directly from declarative knowledge, it is clear that these two aspects of knowledge interact and support each other. The more we welcome opportunities to immerse ourselves in the L2 environment while also reflecting on our declarative knowledge about the L2, the more our brain refines pathways for fluency. We need both and they work together to facilitate our language learning process.

From Concepts to Examples

Now that we know what declarative and procedural knowledge are, let’s explore these ideas with examples about language.

Question: Can you explain the typical order of adjectives in English? Many of you will probably say ‘No’. Let’s find out. We’re going to show you four different examples of different adjective orders in English, and it’s your job to click on the grammatically correct ones. If you grew up speaking English, you actually have a good chance of getting these right just by using your procedural knowledge, i.e. your subconscious, automated knowledge. If English is a language you learned in school, your answers might also rely on your declarative knowledge, i.e. knowledge you know consciously. The exercises will become progressively more difficult but don’t worry. None of this is graded!

Adjective Order in English Exercise

How did that exercise feel? Did you surprise yourself? Hopefully, you found out that you ‘know’ more than you expected about the order of adjectives in English. All English speakers use similar patterns of adjective order every day without even thinking about it. These patterns are not universal across languages or even dialects. Many languages would put these adjectives into different orders, and some dialects of English don’t follow the Standard American English (SAE) adjective order either.

Before explaining more, let’s move on to an example of using declarative knowledge. In this activity, you will need to select the correct homophone. Homophones are words that sound the same but mean different things and are often spelled differently, like ‘night’ and ‘knight’ in English. Just like the previous activity, it’s your job to choose the correct word or part of a word to fill in the blanks. Although some of these answers may seem obvious, some are commonly confused in standard written English and some you may need to look up!

English Homophones Exercise

While the first quiz focused on procedural knowledge, declarative knowledge was essential for the second quiz. There is no way of being able to correctly answer the questions without knowledge of the written English language and its rules which you had to learn explicitly at some point. Even native speakers of English have to learn these differences consciously.

At this point, reflect on your declarative and procedural knowledge in your second language, or any other skill such as art, music, or doing math. Be honest with yourself.

- How much of it is automatic to you? If it is more automatic, it is more likely procedural!

- Can you hold basic conversations about the weather without even thinking about it? If so, that knowledge is procedural!

- Do you have to translate the word for “rain” in your head before you can complain about it to another person? Thinking of translations is an indication of declarative knowledge!

These are just a few examples of declarative and procedural knowledge. Building both of these is important for language learning, and it’s ok if they are slow to develop, especially procedural knowledge, which simply takes practice. This is normal, and monitoring your progress can help you notice your current abilities in both areas.

When setting your goals, assess your current knowledge and consider whether it’s declarative or procedural. If you just learned about a grammar pattern in a language class or on an app, don’t expect this declarative knowledge to suddenly become procedural knowledge without practice. Just like when we’re learning a sport or a musical instrument, knowing what you should do and actually doing it without thinking are two different things! Setting realistic expectations with our current knowledge in mind helps us to learn more efficiently.

References

Carpenter, K., Compton, C., Riddle, E., & Wheatley, J. (2000). A guide to the study of Southeast Asian languages. Journal of Southeast Asian Language Teaching, 9, 1-63. https://seasite.niu.edu/jsealt/pastissues.htm

Lightbown, P., & Spada, N. M. (2013). How languages are learned (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Media Attributions

All original illustrations on this page © Addy Orsi are licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 (Attribution NonCommercial) license.

A word that modifies a noun, usually attributing some characteristics to the noun