2 Chapter 2 – The Quest for Value

Defining the Customer’s Concept of Value

In the previous chapter, Peter Drucker and W. Edward Deming placed the customer at the center of their definitions of the purpose of a business. They used the customer as being at the core of that purpose rather than focusing on financial measures such as profit, return on investment (ROI), or shareholders’ wealth. Drucker’s logic was that if a business did not create a sufficient number of customers, there never would be a profit with the business. Deming argued that delighting customers would become the basis for them to consistently return, and loyalty would ensure that the business would have a higher probability of surviving in the long term. The clearest way of doing that is by focusing on providing your customers with a clear sense of value. This emphasis on value will produce economic benefits. Gale Consulting explains the notion of value this way, “If customers don’t get good value from you, they will shop around to find a better deal.”[1] A recent study put it this way, “These firms have been successful…by consistently creating superior customer value—and profiting handsomely from that customer value.”[2]

Strong evidence indicates that this focus on making the customer central to defining the business translates into economic success. It has been estimated that the cost of gaining a new customer over retaining a current customer is a multiple of five. The costs of regaining a dissatisfied customer over the cost of retaining a customer are ten times as much.[3] So a key question for any business then becomes, “How does one then go about making the customer the center of one’s business?”

What Is Value?

It is essential to recognize that value is not just price. Value is a much richer concept. Fundamentally, the notion of customer value is fairly basic and relatively simple to understand; however, implementing this concept can prove to be tremendously challenging. It is a challenge because customer value is highly dynamic and can change for a variety of reasons, including the following: the business may change elements that are important to the customer value calculation, customers’ preferences and perceptions may change over time, and competitors may change what they offer to customers. One author states that the challenge is to “understand the ever-changing customer needs and innovate to gratify those needs.”[4]

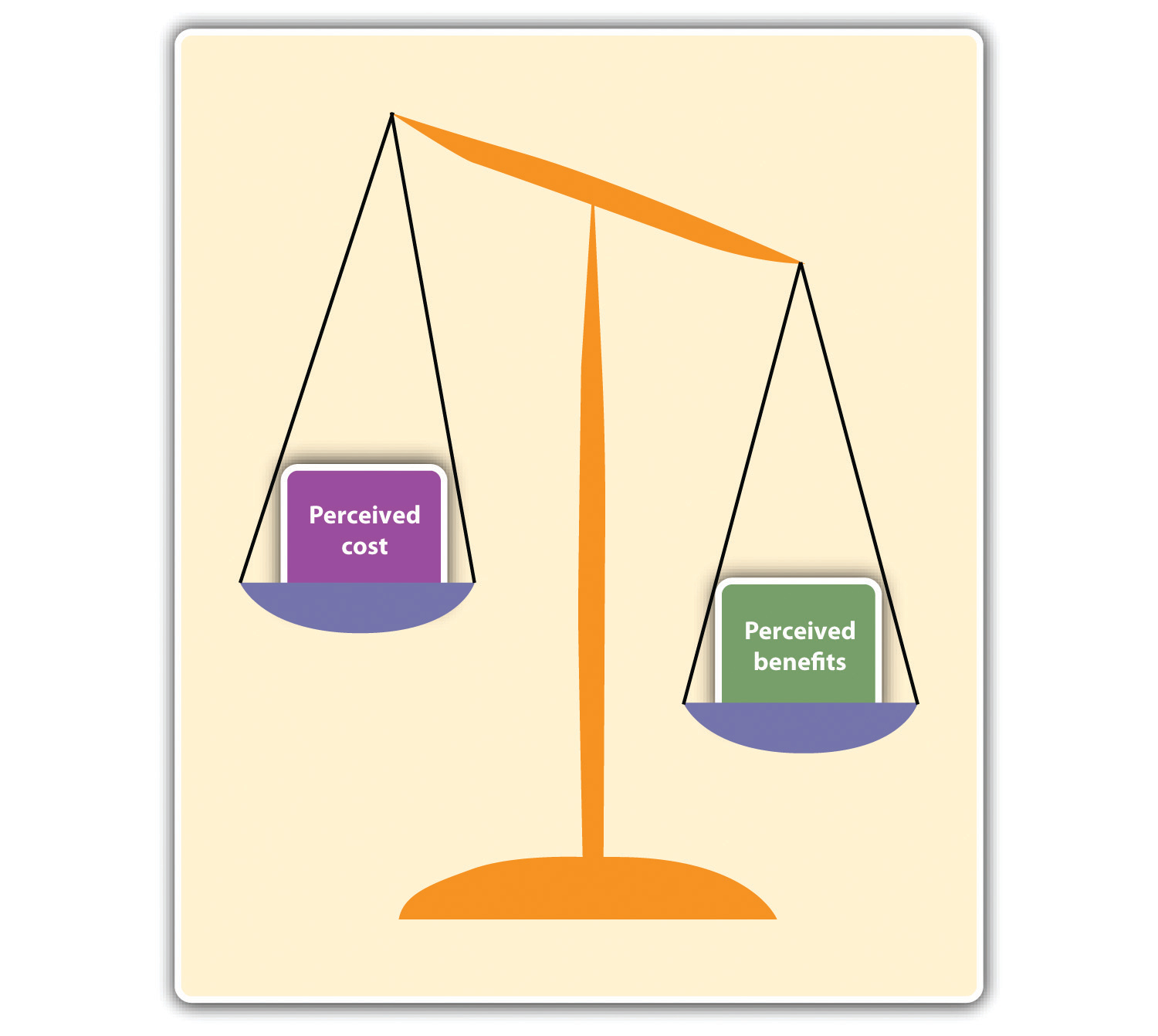

The simple version of the concept of customer value is that individuals evaluate the perceived benefits of some product or service and then compare that with their perceived cost of acquiring that product or service. If the benefits outweigh the cost, the product or the service is then seen as attractive. This concept is often expressed as a straightforward equation that measures the difference between these two values:

customer value = perceived benefits − perceived cost

Perceived Cost versus Perceived Benefits

Some researchers express this idea of customer value not as a difference but as a ratio of these two factors.[5] Either way, it needs to be understood that customers do not evaluate these factors in isolation. They evaluate them with respect to their expectations and the competition.

Firms that provide greater customer value relative to their competitors should expect to see higher revenues and superior returns. Robert Buzzell and Bradley Gale, reporting on one finding in the Profit Impact through Marketing Strategy study, a massive research project involving 2,800 businesses, showed that firms with superior customer value outperform their competitors on ROI and market share gains.[6]

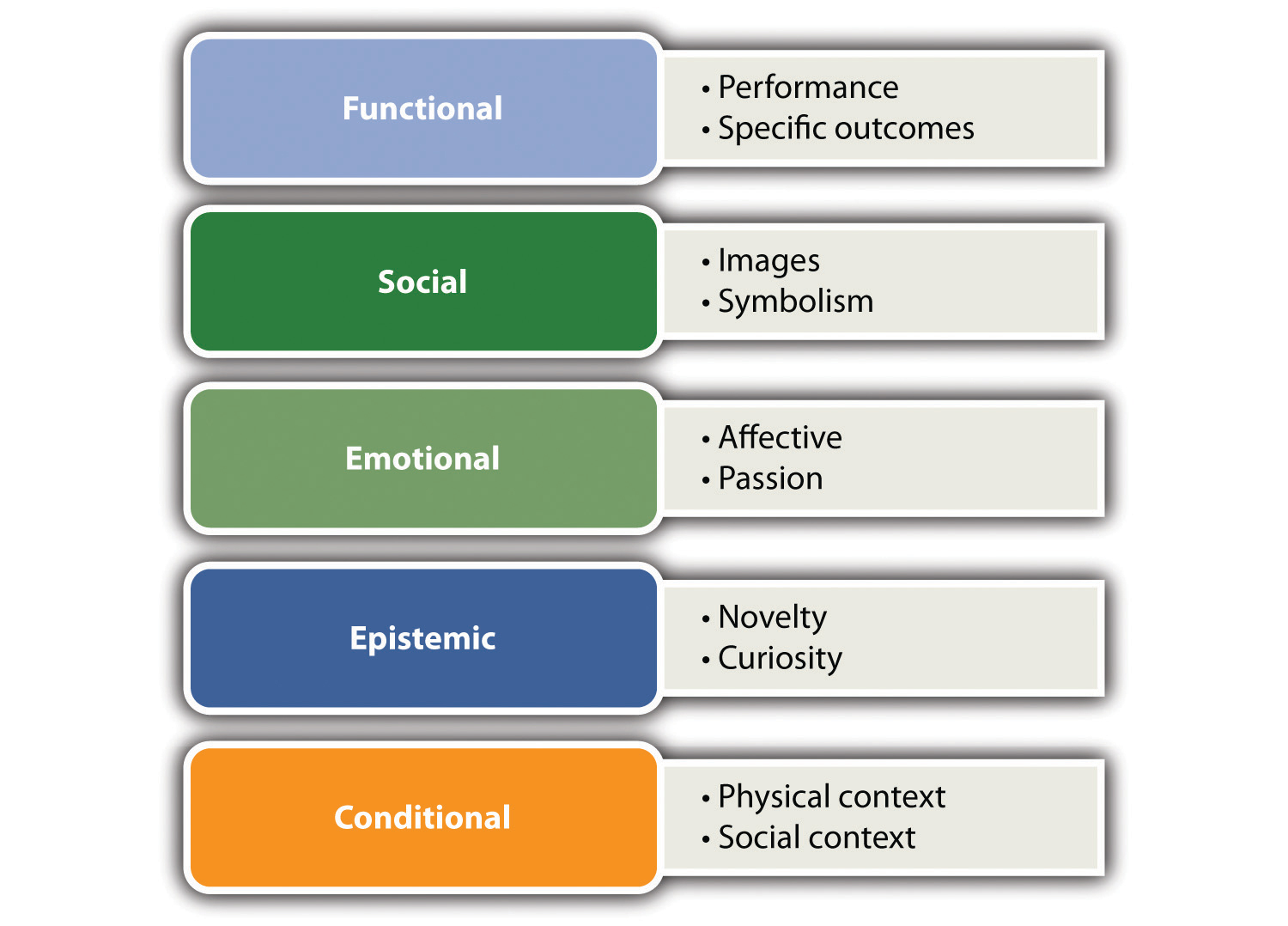

Given this importance, it is critical to understand what makes up the perceived benefits and the perceived costs in the eyes of the consumer. These critical issues have produced a considerable body of research. Some of the major themes in customer value are evolving, and there is no universal consensus or agreement on all aspects of defining these two components. First, there are approaches that provide richly detailed and academically flavored definitions; others provide simpler and more practical definitions. These latter definitions tend to be ones that are closer to the aforementioned equation approach, where customers evaluate the benefits they gain from the purchase versus what it costs them to purchase. However, one is still left with the issue of identifying the specific components of these benefits and costs. In looking at the benefits portion of the value equation, most researchers find that customer needs define the benefits component of value. But there still is no consensus as to what specific needs should be considered. Park, Jaworski, and McGinnis (1986) specified three broad types of needs of consumers that determine or impact value.[7] provided five types of value, as did Woodall (2003), although he did not identify the same five values.[8]. To add to the confusion, Heard (1993–94)[9] identified three factors, while Ulaga (2003)[10] specified eight categories of value; and Gentile, Spiller, and Noci (2007) mentioned six components of value.[11] Smith and Colgate (2007) attempted to place the discussion of customer value in a pragmatic context that might aid practitioners. They identified four types of values and five sources of value. Their purpose was to provide “a foundation for measuring or assessing value creation strategies.”[12] In some of these works, the components or dimensions of value singularly consider the benefits side of the equation, while others incorporate cost dimensions as part of value.

From the standpoint of small businesses, what sense can be made of all this confusion? First, the components of the benefits portion of customer value need to be identified in a way that has significance for small businesses. Second, cost components also need to be identified. Seth, Newman, and Gross’s five types of value provide a solid basis for considering perceived benefits. Before specifying the five types of value, it is critical to emphasize that a business should not intend to compete on only one type of value. It must consider the mix of values that it will offer its customers. (In discussing these five values, it is important to provide the reader with examples. Most of our examples will relate to small business, but in some cases, good examples will have to be drawn from larger firms because they are better known.)

Five Types of Value

Five Types of Value

The five types of value are as follows:

- Functional value relates to the product’s or the service’s ability to perform its utilitarian purpose. Woodruff (1997) identified that functional value can have several dimensions.[13] One dimension would be performance-related. This relates to characteristics that would have some degree of measurability, such as appropriate performance, speed of service, quality, or reliability. A car may be judged on its miles per gallon or the time to go from zero to sixty miles per hour. These concepts can also be seen when evaluating a garage that is performing auto repairs. Customers have an expectation that the repairs will be done correctly, that the car will not have to be brought back for additional work on the same problem, and that the repairs will be done in a reasonable amount of time. Another dimension of functional value might consider the extent to which the product or the service has the correct features or characteristics. In considering the purchase of a laptop computer, customers may compare different models on the basis of weight, battery lifetime, or speed. The notion of features or characteristics can be, at times, quite broad. Features might include aesthetics or an innovation component. Some restaurants will be judged on their ambiance; others may be judged on the creativity of their cuisine. Another dimension of functional value may be related to the final outcomes produced by a business. A hospital might be evaluated by its number of successes in carrying out a particular surgical procedure.

- Social value involves a sense of relationship with other groups by using images or symbols. This may appear to be a rather abstract concept, but it is used by many businesses in many ways. Boutique clothing stores often try to convey a chic or trendy environment so that customers feel that they are on the cutting edge of fashion. Rolex watches try to convey the sense that their owners are members of an economic elite. Restaurants may alter their menus and decorations to reflect a particular ethnic cuisine. Some businesses may wish to be identified with particular causes. Local businesses may support local Little League teams. They may promote fundraising for a particular charity that they support. A business, such as Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream, may emphasize a commitment to the environment or sustainability.

- Emotional value is derived from the ability to evoke an emotional or an affective response. This can cover a wide range of emotional responses. Insurance companies and security alarm businesses are able to tap into both fear and the need for security to provide value. Some theme parks emphasize the excitement that customers will experience with a range of rides. A restaurant may seek to create a romantic environment for diners. This might entail the presence of music or candlelight. Some businesses try to remind customers of a particular emotional state. Food companies and restaurants may wish to stimulate childhood memories or the comfort associated with a home-cooked meal. Häagen-Dazs is currently producing a line of all-natural ice cream with a limited number of natural flavors. It is designed to appeal to consumers’ sense of nostalgia.[14]

- Epistemic value is generated by a sense of novelty or simple fun, which can be derived by inducing curiosity or a desire to learn more about a product or a service. Stew Leonard’s began in the 1920s as a small dairy in Norwalk, Connecticut. Today, it is a $300 million per year enterprise of consisting of four grocery stores. It has been discussed in major management textbooks. These accomplishments are due to the desire to turn grocery shopping into a “fun” experience. Stew Leonard’s uses a petting zoo, animatronic figures, and costumed characters to create a unique shopping environment. They use a different form of layout from other grocery stores. Customers are required to follow a fixed path that takes them through the entire store. Thus customers are exposed to all items in the store. In 1992, they were awarded a Guinness Book world record for generating more sales per square foot than any food store in the United States.[15] Another example of a business that employs epistemic value is Rosetta Stone, a company that sells language-learning software. Rosetta Stone emphasizes the ease of learning and the importance of acquiring fluency in another language through its innovative approach.

- Conditional value is derived from a particular context or a sociocultural setting. Many businesses learn to draw on shared traditions, such as holidays. For the vast majority of Americans, Thanksgiving means eating turkey with the family. Supermarkets and grocery stores recognize this and increase their inventory of turkeys and other foods associated with this period of the year. Holidays become a basis for many retail businesses to tap into conditional value.

Another way businesses may think about conditional value is to introduce a focus on emphasizing or creating a sociocultural context. Business may want to introduce a “tribal” element into their customer base, by using efforts that cause customers to view themselves as a member of a special group. Apple Computer does this quite well. Many owners of Apple computers view themselves as a special breed set apart from other computer users. This sense of special identity helps Apple in the sale of its other electronic consumer products. They reinforce this notion in the design and setup of Apple stores. Harley-Davidson does not just sell motorcycles; it sells a lifestyle. Harley-Davidson also has a lucrative side business selling accessories and apparel. The company supports owner groups around the world. All of this reinforces, among its customers, a sense of shared identity.

It should be readily seen that these five sources of value benefits are not rigorously distinct from each other. A notion of aesthetics might be applied, in different ways, across several of these value benefits. It also should be obvious that no business should plan to compete on the basis of only one source of value benefits. Likewise, it may be impossible for many businesses, particularly start-ups, to attempt to use all five dimensions. Each business, after identifying its customer base, must determine its own mix of these value benefits.

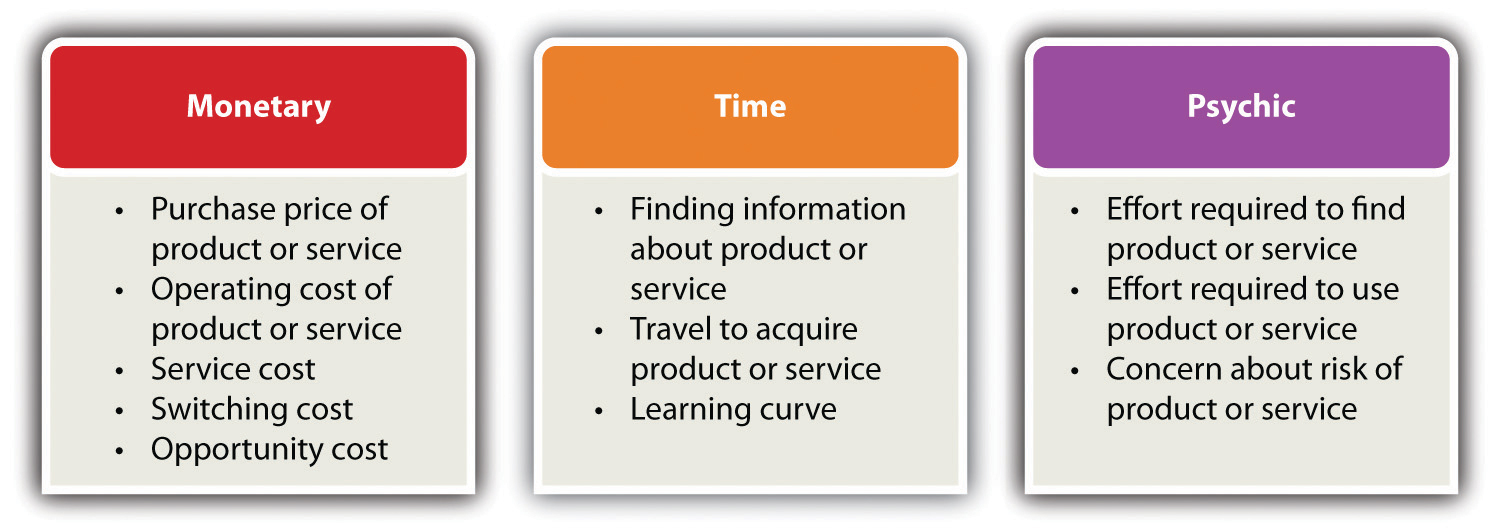

As previously pointed out, the notion of perceived customer value has two components—perceived value benefits and perceived value costs. When examining the cost component, customers need to recognize that it is more than just the cost of purchasing a product or a service. Perceived cost should also be seen having multiple dimensions:

Components of Customer Value

Components of Customer Value

Perceived costs can be seen as being monetary, time, and psychic. The monetary component of perceived costs should, in turn, be broken down into its constituent elements. Obviously, the first component is the purchase price of the product or the service. Many would mistakenly think that this is the only element to be considered as part of the cost component. They fail to consider several other cost components that are quite often of equal—if not greater—importance to customers. Many customers will consider the operating cost of a product or a service. A television cable company may promote an introductory offer with a very low price for the cable box and its installation. Most customers will consider the monthly fees for cable service rather than just looking at the installation cost. They often use service costs when evaluating the value proposition. Customers have discovered that there are high costs associated with servicing a product. If there are service costs, particularly if they are hidden costs, then customers will find significantly less value from that product or service. Two other costs also need to be considered. Switching cost is associated with moving from one provider to another. In some parts of the country, the cost of heating one’s home with propane gas might be significantly less than using home heating oil on an annualized basis. However, this switch from heating oil to propane would require the homeowner to install a new type of furnace. That cost might deter the homeowner from moving to the cheaper form of energy. Opportunity cost involves selecting among alternative purchases. A customer may be looking at an expensive piece of jewelry that he wishes to buy for his wife. If he buys the jewelry, he may have to forgo the purchase of a new television. The jewelry would then be the opportunity cost for the television; likewise, the television would be the opportunity cost for the piece of jewelry. When considering the cost component of the value equation, businesspeople should view each cost as part of an integrated package to be set forth before customers. More and more car dealerships are trying to win customers by not only lowering the sticker price but also offering low-cost or free maintenance during a significant portion of the lifetime of the vehicle.

These monetary components are what we most often think of when we discuss the term cost, and, of course, they will influence the decision of customers; however, the time component is also vital to the decision-making process. Customers may have to expend time acquiring information about the nature of the product or the service or make comparisons between competing products and services. Time must be expended to acquire the product or the service. This notion of time would be associated with learning where the product or the service could be purchased. It would include time spent traveling to the location where the item would be purchased or the time it takes to have the item delivered to the customer. One also must consider the time that might be required to learn how to use the product or the service. Any product or service with a steep learning curve might deter customers from purchasing it. Firms can provide additional value by reducing the time component. They could simplify access to the product or the service. They may offer a wide number of locations. Easy-to-understand instructions or simplicity in operations may reduce the amount of time that is required to learn how to properly use the product or the service.

The psychic component of cost can be associated with those factors that might induce stress on the customer. There can be stress associated with finding or evaluating products and services. In addition, products or services that are difficult to use or require a long time to learn how to use properly can cause stress on customers. Campbell’s soup introduced a meal product called Souper Combos, which consisted of a sandwich and a cup of soup. At face value, one would think that this would be a successful product. Unfortunately, there were problems with the demands that this product placed on the customer in terms of preparing the meal. The frozen soup took twice as long to microwave as anticipated, and the consumer had to repeatedly insert and remove both the soup and the sandwich from the microwave.[16]

In summary, business owners need to constantly consider how they can enhance the benefits component while reducing the cost components of the value equation. The table below summarizes the subcomponents of perceived value, the types of firms that emphasize those components, and the activities that might be necessary to either enhance benefits or reduce costs.

Components of Perceived Benefit and Perceived Cost

Components of Perceived Benefit:

| Component | Aspects | Activities to Deliver |

|---|---|---|

| Functional |

|

|

| Social |

|

|

| Emotional |

|

|

| Epistemic |

|

|

| Conditional |

|

|

Components of Perceived Cost:

| Component | Aspects | Activities to Deliver |

|---|---|---|

| Monetary |

|

|

| Time |

|

|

| Psychic |

|

|

Different Customers—Different Definitions

It is a cliché to say that people are different; nonetheless, it is true to a certain extent. If all people were totally distinct individuals, the notion of customer value might be an interesting intellectual exercise, but it would be absolutely useless from the standpoint of business because it would be impossible to identify a very unique definition of value for every individual. Fortunately, although people are individuals, they often operate as members of groups that share similar traits, insights, and interests. This notion of customers being members of some type of group becomes the basis of the concept known as Market segmentation. This involves dividing the market into several portions that are different from each other.[17] It simply involves recognizing that the market at large is not homogeneous. There can be several dimensions along which a market may be segmented: geography, demographics, psychographics, or purchasing behavior. Geographic segmentation can be done by global or national region, population size or density, or even climate. Demographic segmentation divides a market on factors such as gender, age, income, ethnicity, or occupation. Psychographic segmentation is carried out on dimensions that reflect differences in personality, opinions, values, or lifestyle. Purchasing behavior can be another basis for segmentation. Differences among customers are determined based on a customer’s usage of the product or the service, the frequency of purchases, the average value of purchases, and the status as a customer—major purchaser, first-time user, or infrequent customer. In the business-to-business (B2B) environment, one might want to segment customers on the basis of the type of company.

Market segmentation recognizes that not all people of the same segment are identical; it facilitates a better understanding of the needs and wants of particular customer groups. This comprehension should enable a business to provide greater customer value. There are several reasons why a small business should be concerned with market segmentation. The main reason centers on providing better customer value. This may be the main source of competitive advantage for a small business over its larger rivals. Segmentation may also indicate that a small business should focus on particular subsets of customers. Not all customers are equally attractive. Some customers may be the source of most of the profits of a business, while others may represent a net loss to a business. The requirements for providing value to a first-time buyer may differ significantly from the value notions for long time, valued customer. A failure to recognize differences among customers may lead to significant waste of resources and might even be a threat to the very existence of a firm.

Key Takeaways

- Essential to the success of any business is the need to correctly identify customer value.

- Customer value can be seen as the difference between a customer’s perceived benefits and the perceived costs.

- Perceived benefits can be derived from five value sources: functional, social, emotional, epistemic, and conditional.

- Perceived costs can be seen as having three elements: monetary, time, and psychic.

- To better provide value to customers, it may be necessary to segment the market.

- Market segmentation can be done on the basis of demographics, psychographics, or purchasing behavior.

Knowing Your Customers

The perceived value proposition offers a significant challenge to any business. It requires that a business have a fairly complete understanding of the customer’s perception of benefits and costs. Although market segmentation may help a business better understand some segments of the market, the challenge is still getting to understand the customer. In many cases, customers themselves may have difficulty in clearly understanding what they perceive as the benefits and costs of any offer. How then is a business, particularly a small business, to identify this vital requirement? The simple answer is that a business must be open to every opportunity to listen to the voice of the customer (VOC). This may involve actively talking to your customers on a one-to-one basis, as illustrated by Robert Brown, the small business owner highlighted at the beginning of this chapter. It may involve other methods of soliciting feedback from your customers, such as satisfaction surveys or using the company’s website. Businesses may engage in market research projects to better understand their customers or evaluate proposed new products and services. Regardless of what mechanism is used, it should serve one purpose—to better understand the needs and wants of your customers.

Research

Good research in the area of customer value simply means that one must stop talking to the customer—talking through displays, advertising, and/or a website. It means that one is always open to listening carefully to the VOC. Active listening in the service of better identifying customer value means that one is always open to the question of how your business can better solve the problems of particular customers.

If businesses are to become better listeners, what should they be listening for? What types of questions should they be asking their customers? Businesses should address the following questions when they attempt to make customer value the focus of their existence:

- What needs of our customers are we currently meeting?

- What needs of our customers are we currently failing to meet?

- Do our customers understand their own needs and are they aware of them?

- How are we going to identify those unmet customer needs?

- How are we going to listen to the VOC?

- How are we going to let the customer talk to us?

- What is the current value proposition that is desired by customers?

- How is the value proposition different for different customers?

- How—exactly—is our value proposition different from our competitors?

- Do I know why customers have left our business for our competitors?

Finding Your Customer

At the beginning of this chapter, it was argued that your central focus must be the customer. One critical way that this might be achieved is by providing a customer with superior value. However, creating this value must be done in a way that assures that the business makes money. One way of doing this is by identifying and selecting those customers who will be profitable. Some have put forth the concept of customer lifetime value (CLV), a measure of the revenue generated by a customer, the cost generated for that particular customer, and the projected retention rate of that customer over his or her lifetime.[18]

This concept is popular enough that there are lifetime value calculator templates available on the web. These calculators look at the cost of acquiring a customer and then compute the net present value of the customer during his or her lifetime. Net present value discounts the value of future cash flows. It recognizes the time value of money. You can use one of two models: a simple model that examines a single product or a more complex model with additional variables. One of the great benefits of conducting customer lifetime value analysis is combining it with the notion of market segmentation. The use of market segmentation allows for recognizing that certain classes of customers may produce significantly different profits during their lifetimes. Not all customers are the same.

Let us look at a simple case of segmentation based on behavioral factors. Some customers make more frequent purchases; these loyal customers may generate a disproportionate contribution to a firm’s overall profit. It has been estimated that only 15 percent of American customers have loyalty to a single retailer, yet these customers generate between 55 percent and 70 percent of retail sales.[19] Likewise, a lifetime-based economic analysis of different customer segments may show that certain groups of customers actually cost more than the revenues that they generate.

Having segmented your customers, you will probably find that some require more handholding during and after the sale. Some customer groups may need you to “tailor” your product or service to their needs.[20] As previously mentioned, market segmentation can be done along several dimensions. Today, some firms use data mining to determine the basis of segmentation, but that often requires extensive databases, software, and statisticians. One simple way to segment your customers is the customer value matrix that is well suited for small retail and service businesses. It uses just three variables: recency, frequency, and monetary value. Its data requirements are basic. It needs customer identification, the date of purchase, and the total amount of purchase. This enables one to easily calculate the average purchase amount of each customer. From this, you can create programs that reach out to particular segments.[21]

What Your Gut Tells You

The role of market research was already discussed in this chapter. For many small businesses, particularly very small businesses, formal market research may pose a problem. In many small businesses, there may be a conflict between decision-making made on a professional basis and decision-making made on an instinctual basis.[22] Some small business owners will always decide based on a gut instinct. We can point to many instances in which gut instinct concerning the possible success in product paid off, whereas a formal market research evaluation might consider the product to be a nonstarter.

In 1975, California salesman Gary Dahl came up with the idea of the ideal pet—a pet that would require minimal care and cost to maintain. He developed the idea of the pet rock. This unlikely concept became a fad and a great success for Dahl. Ken Hakuta, also known as Dr. Fad, developed a toy known as the Wallwalker in 1983. It sold over 240 million units.[23] These and other fad products, such as the Cabbage Patch dolls and Rubik’s Cube, are so peculiar that one would be hard-pressed to think of any marketing research that would have indicated that they would be viable, let alone major successes.

Sometimes it is an issue of having a product idea and knowing where the correct market for the product will be. Jill Litwin created Peas a Pie Pizza, which is a natural food pizza pie with vegetables baked in the crust. She knew that the best place to market her unique product would be in the San Francisco area with its appreciation of organic foods.[24]

This notion of going with one’s gut instinct is not limited to fad products. Think of the birth of Apple Computer. The objective situation was dealing with a company whose two major executives were college dropouts. The business was operating out of the garage of the mother of one of these two executives. They were producing a product that up to that point had only a limited number of hobbyists as a market. None of this would add up to very attractive prospect for investment. You could easily envision a venture capitalist considering a possible investment asking for a market research study that would identify the target market(s) for its computers. None existed at the company’s birth. Even today, there is a strong indication that Apple does not rely heavily on formal marketing research. As Steve Jobs put it, “It’s not about pop culture, it’s not about fooling people, and it’s not about convincing people that they want something they don’t. We figure out what we want. And I think we’re pretty good at having the right discipline to think through whether a lot of other people are going to want it, too. That’s what we get paid to do. So you can’t go out and ask people, you know, what’s the next big [thing.] There is a great quote by Henry Ford, right? He said, “If I had asked my customers what they wanted, they would’ve told me ‘A faster horse.’”[25]

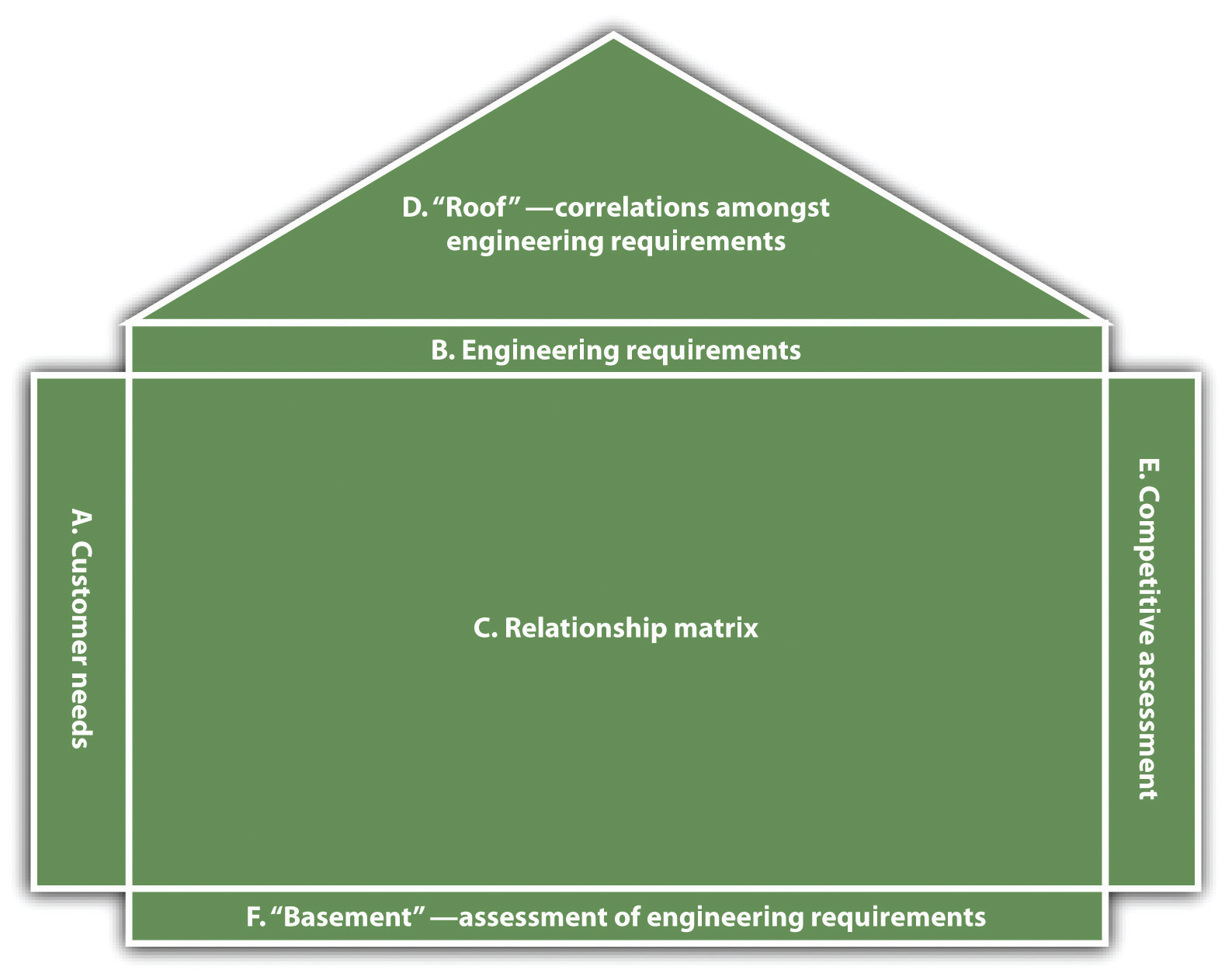

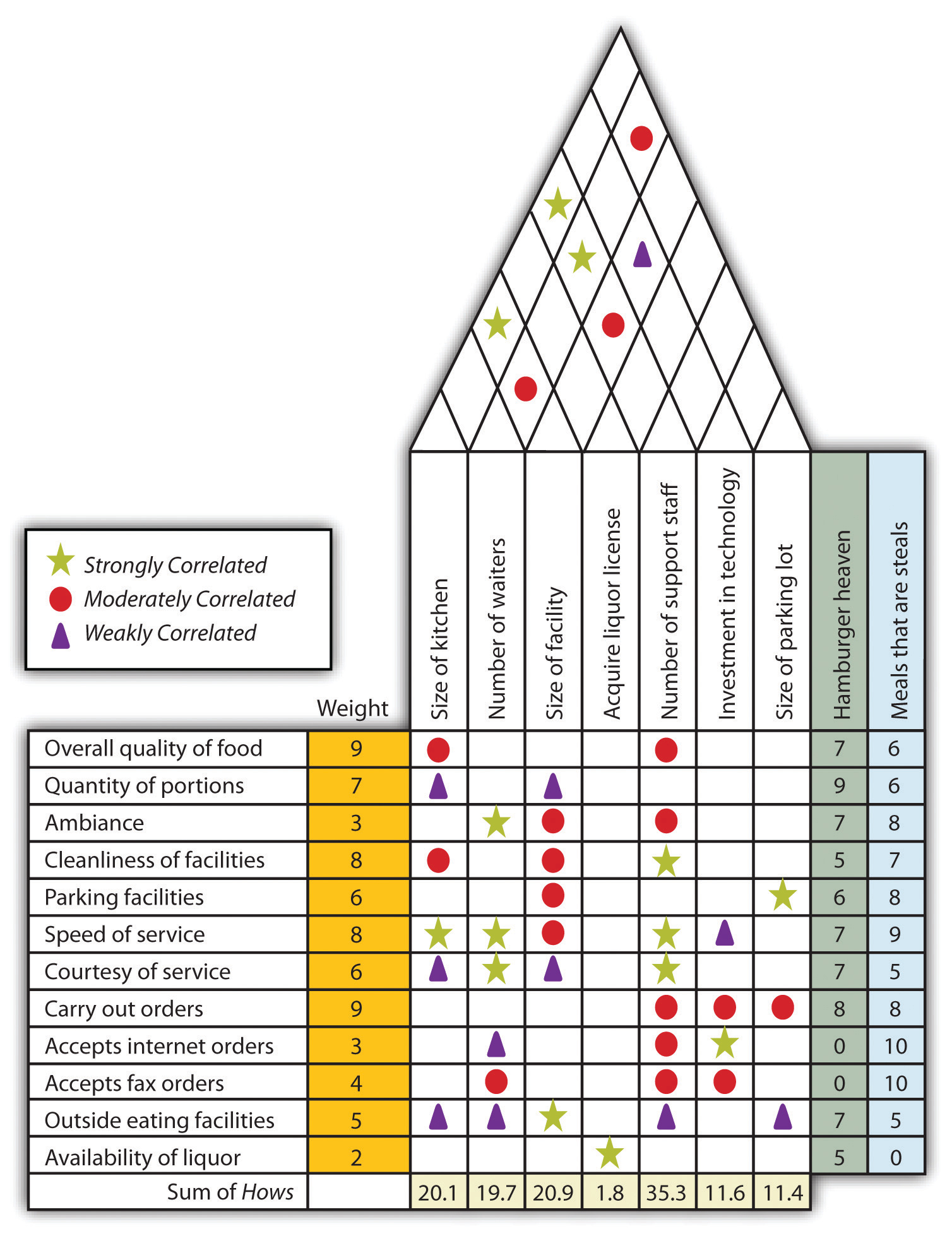

The Voice of the Customer—QFD

Quality function deployment (OFD) is an approach that is meant to take the VOC concept seriously and uses it to help design new products and services or improve existing ones. It is an approach that was initially developed in Japan for manufacturing applications. It seeks “to transform user demands into design quality, to deploy the functions forming quality, and to deploy methods for achieving the design quality into subsystems and component parts, and ultimately to specific elements.”[26] To put it more clearly, QFD takes the desires of consumers and explores how well the individual activities of the business are meeting those desires. It also considers how company activities interact with each other and how well the company is meeting those customer desires with respect to the competition. It achieves all these ends through the means of a schematic; see below, which is known as the house of quality. The schematic provides the backbone for the entire QFD process. A comprehensive design process may use several houses of quality, moving from the first house, which concentrates on the initial specification of customer desires, all the way down to developing a house that focuses on the specification for parts or processes. Any house is composed of several components:

- Customer requirements (the whats). Here you identify the elements desired by customers; this section also contains the relative importance of these needs as identified by customers.

- Engineering characteristics (the hows). This is the means by which an organization seeks to meet customer needs.

- Relationship matrix. This illustrates the correlations among customer requirements and engineering characteristics. The degree of the correlation may be represented by different symbols.

- “Roof” of the house. This section illustrates the correlations among the engineering characteristics and reveals synergies that might exist among the engineering characteristics.

- Competitive assessment matrix. This is used to evaluate the position of a business with respect to its competition.

- “Basement.” This section is used for assessing the engineering characteristics or setting target values. The “basement” enables participants to instantly see the relative benefits of the activities undertaken by a company in meeting consumer desires by multiplying the values in each cell by the weight of the “why” and then adding the values together.

House of Quality

Although it might initially appear to be complex, QFD provides many benefits, including the following: (1) reduces time and effort during the design phase, (2) reduces alterations in design, (3) reduces the entire development time, (4) reduces the probability of inept design, (5) assists in team development, and (6) helps achieve common consensus.[27]

Unfortunately, QFD is most often associated with manufacturing. Few realize that it has found wide acceptance in many other areas—software development, services, education, amusement parks, restaurants, and food services. (Visit this website for examples of these applications of QFD.) Further, company size should not be seen as a limitation to its possible application. The QFD approach, in a simplified form, can be easily and successfully used by any business regardless of its size.[28] Its visual nature makes it extremely easy to comprehend, and it can convey to all members of the business the relative importance of the elements and what they do to help meet customers’ expectations.

Simplified House of Quality for a Restaurant

Although some succeed by listening to their instincts—their inner voices—it is highly advisable for all businesses to be proactive in trying to listen to the VOC. Listening to the customer is the domain of market research. However, it should not be surprising that many small businesses have severe resource constraints that make it difficult for them to use complex and sophisticated marketing and market research approaches.[29] To some extent, this is changing with the introduction of powerful, yet relatively low cost, web-based tools, and social media. Another restriction that a small business may face in the area of marketing is that the owner’s marketing skills and knowledge may not be very extensive. The owners of such firms may opt for several types of solutions. They may try to mimic the marketing techniques employed by larger organizations, drawing on what was just mentioned. They may opt for sophisticated but easy to use analytical tools, or they may just simply take marketing tools and techniques and apply them to the small business environment.[30]

The most basic and obvious way to listen to customers is by talking to them. All businesses should support programs in which employees talk to customers and then record what they have to say about the product or the service. It is important to centralize these observations.

Other ways of listening to customers are through comment cards and paper and online surveys. These approaches have their strengths and limitations. Regardless of these limitations, they do provide an insight into your customers. Another way one can gather information about customers is through loyalty programs. Loyalty programs are used by 81 percent of US households.[31] Social media options offer a tremendous opportunity to not only listen to your customer but also engage in an active dialog that can build a sustainable relationship with customers.

Key Takeaways

- Businesses must become proactive in attempting to identify the value proposition of their customers. They must know how to listen to the VOC.

- Businesses must make every effort to identify the unmet needs of their customers.

- Businesses should recognize that customer segmentation would enable them to better provide customer value to their various customers.

- Businesses should think in terms of computing the customer lifetime value within different customer segments.

- Intuition can play an important role in the development of new products and services.

- Tools and techniques such as QFD assist in the design of products and services so that a business may be better able to meet customer expectations.

- Innovation can play a key role in creating competitive advantage for small businesses.

- Innovation does not require a huge investment; it can be done by small firms by promoting creativity throughout the organization.

- Small businesses must be open to new social and consumer trends. Readily available technology can help them in identifying such trends.

Sources of Business Ideas

Small businesses have always been a driver of new products and services. Many products and inventions that we might commonly associate with large businesses were originally created by small businesses, including air-conditioners, Bakelite, the FM radio, the gyrocompass, the high resolution computed axial tomography scanner, the outboard engine, the pacemaker, the personal computer, frozen food, the safety razor, soft contact lenses, and the zipper.[32] This creativity and innovative capability probably stems from the fact that smaller businesses, which may lack extensive financial resources, bureaucratic restraints, or physical resources, may find a competitive edge by providing customers value by offering new products and services. It is therefore important to consider how small businesses can foster a commitment to creativity and innovation.

Creativity and Innovation

One way smaller firms may compete with their larger rivals is by being better at the process of innovation, which involves creating something that is new and different. It need not be limited to the creation of new products and services. Innovation can involve new ways in which a product or a service might be used. It can involve new ways of packaging a product or a service. Innovation can be associated with identifying new customers or new ways to reach customers. To put it simply, innovation centers on finding new ways to provide customer value.

Although some would argue that there is a difference between creativity and innovation, one would be hard-pressed to argue that creativity is not required to produce innovative means of constructing customer value. An entire chapter, even an entire book, could be devoted to fostering creativity in a small business. This text will take a different track; it will look at those factors that might inhibit or kill creativity. Alexander Hiam (1998) identified nine factors that can impede the creative mind-set in organizations:[33]

- Failure to ask questions. Small-business owners and their employees often fail to ask the required why-type questions.

- Failure to record ideas. It does not help if individuals in an organization are creative and produce a large number of ideas but other members of the organization cannot evaluate these ideas. Therefore, it is important for you to record and share ideas.

- Failure to revisit ideas. One of the benefits of recording ideas is that if they are not immediately implemented, they may become viable at some point in the future.

- Failure to express ideas. Sometimes individuals are unwilling to express new ideas for fear of criticism. In some organizations, we are too willing to critique an idea before it is allowed to fully develop.

- Failure to think in new ways. This is more than the cliché of “thinking outside the box.” It involves new ways of approaching and looking at the problem of providing customer value.

- Failure to wish for more. Satisfaction with the current state of affairs or with the means of solving particular problems translates into an inability to look at new ways of providing value to customers.

- Failure to try to be creative. Many people mistakenly think that they are not at all creative. This means you will never try to produce new types of solutions to the ongoing problems.

- Failure to keep trying. When attempting to provide new ways to create customer value, individuals are sometimes confronted with creative blocks. Then they simply give up. This is the surest way to destroy the creative thinking process.

- Failure to tolerate creative behavior. Organizations often fail to nurture the creative process. They fail to give people time to think about problems; they fail to tolerate the “odd” suggestions from employees and limit creativity to a narrow domain.

One of the great mistakes associated with the concept of innovation is that innovation must be limited to highly creative individuals and organizations with large research and development (R&D) facilities.[34] The organization’s size may have no bearing on its ability to produce new products and services. More than a decade ago, studies began to indicate that small manufacturing firms far exceeded their larger counterparts with respect to the number of innovations per employee.[35]

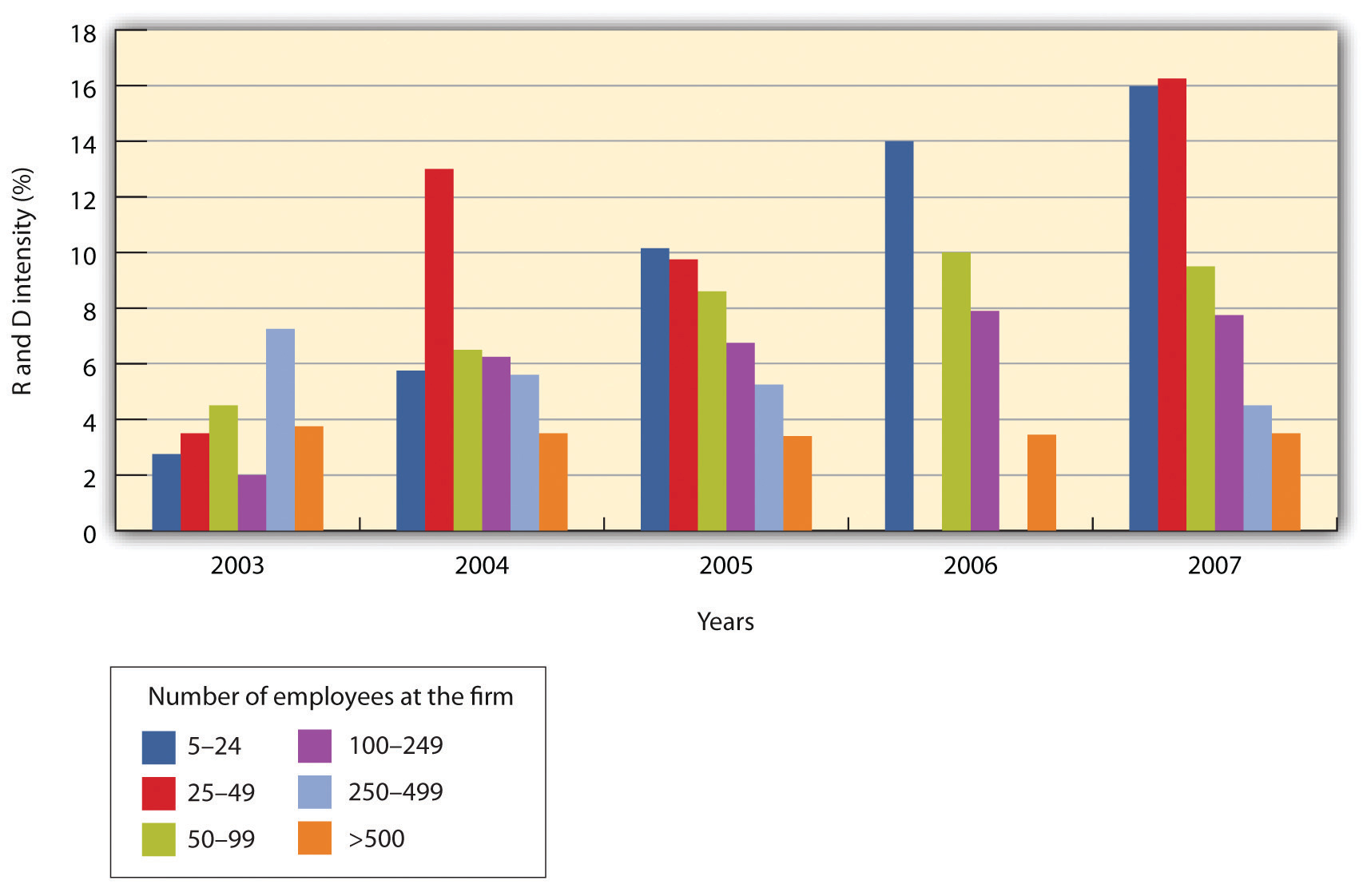

A more recent study, which covered the period from 2003 to 2007, showed that R&D performance by small US companies grew slightly faster than the comparable performance measures for larger US firms. During that period, small firms increased their R&D spending by more than 40 percent, compared to an approximate 33 percent increase for large companies. These smaller firms also increased their employment of scientists and engineers at a rate approximately 75 percent greater than larger companies. Further, the results of this study, which are presented in “R&D Intensity by Firm Size”, illustrate that particularly since 2004, smaller businesses have outpaced their larger rivals with respect to R&D intensity. The term R&D intensity refers to the current dollars spent on R&D divided by a company’s reported sales revenue.<[36]

R&D Intensity by Firm Size

It cannot be overemphasized that innovation should not be limited to the creation of products or services. The following are just a few examples of innovation beyond the development of new products:

- In 1965, Thomas Angove, an Australian winemaker, developed the idea of packaging wine in boxes that had a polyethylene bladder. The package was not only more convenient to carry but also kept the wine fresher for a longer period of time.[37]

- Apple’s iPod was certainly an innovative product, but its success was clearly tied to the creation of the iTunes website that provided content.

- Baker Tweet alerts customers via Twitter any time a fresh batch of baked goods emerge from a participating baker’s oven.[38]

- Patrons at Wagaboo restaurants in Madrid can book specific tables online.[39]

- Restaurants often mark up bottles of wine by 200 percent to 300 percent. Several restaurants in New York, Sydney, and London have developed relationships with wine collectors. The collectors may have more wine than they can possibly drink, so they offer the wine for sale in the restaurant, with the restaurant selling it at a straightforward markup of 35 percent. This collaboration with customers is beneficial for the wine collector, the restaurant, and the customer.

Social and Consumer Trends

Not all businesses have to concern themselves with social and consumer trends. Some businesses, and this would include many small businesses, operate in a relatively stable environment and provide a standard good or service. The local luncheonette is expected to provide standard fare on its menu. The men’s haberdasher will be expected to provide mainline men’s clothing. However, some businesses, particularly smaller businesses, could greatly benefit by recognizing an emerging social or consumer trend. Small businesses that focus on niche markets can gain sales if they can readily identify new social and consumer trends.

Trends differ from fads. Fads may delight customers, but by their very nature, they have a short shelf life. Trends, on the other hand, may be a portend of the future.[40] Smaller businesses may be in a position to better exploit trends. Their smaller size can give them greater flexibility; because they lack an extensive bureaucratic structure, they may be able to move with greater rapidity. The great challenge for small businesses is to be able to correctly identify these trends in a timely fashion. In the past, businesses had to rely on polling institutes for market research as a way of attempting to identify social trends. Harris Interactive produced a survey about the obesity epidemic in America. This study showed that the vast majority of Americans over the age of 25 are overweight. The percentage of those overweight has steadily increased since the early 1980s. The study also indicated that a majority of these people desired to lose weight. This information could be taken by the neighborhood gym, which could then create specialized weight-loss programs. Recognizing this trend could lead to a number of different products and services.[41]

In the past, the major challenge for smaller businesses to identify or track trends was the expense. These firms would have to use extensive market research or clipping services. Today, many of those capabilities can be provided online, either at no cost or a nominal cost.[42] Google Trends tracks how often a particular topic has been searched on Google for a particular time horizon. The system also allows you to track multiple topics, and it can be refined so that you can examine particular regions with these topics searched. The data are presented in graphical format that makes it easy to determine the existence of any particular trends. Google Checkout Trends monitors the sales of different products by brand. One could use this to determine if seasonality exists for any particular product type. Microsoft’s AdCenter Labs offers two products that could be useful in tracking trends. One tool—Search Volume—tracks searches and also provides forecasts. Microsoft’s second tool—Keyword Forecast—provides data on actual searches and breaks it down by key demographics. Facebook provides a tool called Lexicon. It tracks Facebook’s communities’ interests. (Check out the Unofficial Facebook Lexicon Blog for a description on how to fully use Lexicon.) The tool Twist tracks Twitter posts by subject areas. Trendpedia will identify articles online that refer to particular subject areas. These data can be presented as a trend line so that one can see the extent of public interest over time. The trend line is limited to the past three months. Trendrr tracks trends and is a great site for examining the existence of trends in many areas.

Online technology now provides even the smallest business with the opportunity to monitor and detect trends that can be translated into more successful business ventures.

Websites

Key Takeaways

- Small businesses must be open to innovation with respect to products, services, marketing methods, and packaging.

- Creativity in any organization can be easily stifled by a variety of factors. These should be avoided at all cost.

- Small businesses should be sensitive to the emergence of new social and consumer trends.

- Online databases can provide even the smallest of businesses with valuable insights into the existence and emergence of social and consumer trends.

Image Descriptions

Figure 2.3 Components of Customer Value. Three slides:

- Monetary

- Purchase price of product or service

- Operating cost of product or service

- Service cost

- Switching cost

- Opportunity cost

- Time

- Finding information about product or service

- Travel to acquire product or service

- Learning curve

- Psychic

- Effort required to find product or service

- Effort required to use product or service

- Concern about risk of product or service

Figure 2.5 Simplified House of Quality for a Restaurant Example: a table, shaped like a house, that shows a summary of different quality components and how these components are correlated to concrete elements of the restaurant like it’s size and staff. Blank cells indicate no correlation. The original table uses a color coded symbols and a key, which are directly translated in this version:

| House of quality category | Weight | Size of Kitchen | Number of Waiters | Size of facility | Acquire liquor license | Number of Support staff | Investment in Technology | Size of Parking Lot | Hamburger heaven | Meals that are steals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall quality of food | 9 | moderately correlated | moderately correlated | 7 | 6 | |||||

| Quantity of portions | 7 | weakly correlated | weakly correlated | 9 | 6 | |||||

| Ambiance | 3 | strongly correlated | moderately correlated | moderately correlated | 7 | 8 | ||||

| Cleanliness of facilities | 8 | moderately correlated | moderately correlated | strongly correlated | 5 | 7 | ||||

| Parking facilities | 6 | moderately correlated | strongly correlated | 6 | 8 | |||||

| Speed of service | 8 | strongly correlated | strongly correlated | moderately correlated | strongly correlated | weakly correlated | 7 | 9 | ||

| Courtesy of Service | 6 | weakly correlated | strongly correlated | weakly correlated | strongly correlated | 7 | 5 | |||

| Carry out orders | 9 | moderately correlated | moderately correlated | moderately correlated | 8 | 8 | ||||

| Accepts internet orders | 3 | weakly correlated | moderately correlated | strongly correlated | 0 | 10 | ||||

| Accepts fax orders | 4 | moderately correlated | moderately correlated | moderately correlated | 0 | 10 | ||||

| Outside eating facilities | 5 | weakly correlated | weakly correlated | strongly correlated | weakly correlated | weakly correlated | 7 | 5 | ||

| Availability of liquor | 2 | strongly correlated | 5 | 0 | ||||||

| Sum of *Hows* | N/A | 20.1 | 19.7 | 20.9 | 1.8 | 35.3 | 11.6 | 11.4 | N/A | N/A |

Figure 2.6 R&D Intensity by Firm Size Clustered Bar chart. For every year from 2003 to 2007 this chart presents the R and D intensity percentage for firms of different sizes. Firms with 5-24 employees starts with an R&D around 2% which increases by 2-5% each year, nearing 16% in 2007. Firms with 25-49 employees start near 3% , jump to 13% in 2004, fall in 2005 and 2006, and jump to 16% in 2007. Firms with 50-99 employees consistently increase their R&D% from 4% in 2003 to 10% in 2006, with a slight drop in 2007. Firms with 250-499 employees go against the trend dropping from 7% in 2003 to just over 4% in 2007. Firms with over 500 employees remain relatively consistent between 3% and 4% every year.

- “Why Customer Satisfaction Fails,” Gale Consulting, accessed December 2, 2011, www.galeconsulting.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id= 18&Itemid=23. ↵

- George Day and Christine Moorman, Strategy from the Outside In (New York: McGraw Hill, Kindle Edition, 2010), 104–10. ↵

- Forler Massnick, The Customer Is CEO: How to Measure What Your Customers Want—and Make Sure They Get It (New York: Amacom, 1997), 76. ↵

- Sudhakar Balachandran, “The Customer Centricity Culture: Drivers for Sustainable Profit,” Course Management 21, no. 6 (2007): 12. ↵

- M. Christopher, “From Brand Value to Customer Value,” Journal of Marketing Practice: Applied Marketing Science 2, no. 1 (1996): 55. ↵

- Robert D. Buzzell and Bradley T. Gale, The PIMS Principles—Linking Strategy to Performance (New York: Free Press, 1987), 106. ↵

- C. Whan Park, Bernard J. Jaworski, and Deborah J. MacInnis, “Strategic Brand Concept Image Management,” Journal of Marketing 50 (1986): 135. Seth, Newman, and Gross (1991)Jagdish N. Seth, Bruce I. Newman, and Barbara L. Gross, Consumption Values and Market Choice: Theory and Applications (Cincinnati, OH: Southwest Publishing, 1991), 77. ↵

- Tony Woodall, “Conceptualising ‘Value for the Customer’: An Attributional, Structural and Dispositional Analysis,” Academy of Marketing Science Review 2003, no. 12 (2003), accessed October 7, 2011, www.amsreview.org/articles/woodall12-2003.pdf. ↵

- Ed Heard, “Walking the Talk of Customers Value,” National Productivity Review 11 (1993–94): 21. ↵

- Wolfgang Ulaga, “Capturing Value Creation in Business Relationships: A Customer Perspective,” Industrial Marketing Management 32, no. 8 (2003): 677. ↵

- Chiara Gentile, Nicola Spiller, and Giuliana Noci, “How to Sustain the Customer Experience: An Overview of Experience Components That Co-Create Value with the Customer,” European Management Journal 25, no. 5 (2007): 395. ↵

- J. Brock Smith and Mark Colgate, “Customer Value Creation: A Practical Framework,” Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 15, no. 1 (2007): 7. ↵

- Robert B. Woodruff, “Customer Value: The Next Source of Competitive Advantage, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 25, no. 2 (1997): 139. ↵

- “Maturalism,” Trendwatching.com, accessed June 1, 2012, http://trendwatching.com/trends/maturialism/. ↵

- “Company Story,” Stew Leonards, accessed October 7, 2011, www.stewleonards.com/html/about.cfm. ↵

- Calvin L. Hodock, Why Smart Companies Do Dumb Things (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2007), 65. ↵

- “Market Segmentation,” NetMBA Business Knowledge Center, accessed October 7, 2011, www.netmba.com/marketing/market/segmentation. ↵

- Jack Schmid, “How Much Are Your Customers Worth?,” Catalog Age 18, no. 3 (2001): 63. Jonathon Lee and Lawrence Feick, “Cooperating Word-of-Mouth Affection Estimating Customer Lifetime Value,” Journal of Database Marketing and Customer Strategy Management 14 (2006): 29. ↵

- “Loyalty Promotions,” Little & King Integrated Marketing Group, accessed December 5, 2011, www.littleandking.com/white_papers/loyalty_promotions.pdf. ↵

- “Determining Your Customer Perspective—Can You Satisfy These Customer Segments?,” Business901.com, accessed October 8, 2011, business901.com/blog1/determining-your-customer-perspective-can-you-satisfy-these-customer-segments. ↵

- Claudio Marcus, “A Practical yet Meaningful Approach to Customer Segmentation,” Journal of Consumer Marketing 15, no. 5 (1998): 494. ↵

- Malcolm Goodman, “The Pursuit of Value through Qualitative Market Research,” Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 2, no. 2 (1999): 111. ↵

- “What Are Wacky WallWalkers?,” DrFad.com, accessed December 2, 2011, www.drfad.com/fad_facts/wallwalker.htm. ↵

- Susan Smith Hendrickson, “Mining Her Peas and Carrots Wins Investors,” Mississippi Business Journal 32, no. 21 (2010): S4. ↵

- Alain Breillatt, “You Can’t Innovate Like Apple,” Pragmatic Marketing 6, no. 4, accessed October 8, 2011, www.pragmaticmarketing.com/publications/magazine/6/4/you_cant_innovate_like_apple. ↵

- Yoji Akao, Quality Function Deployment: Integrating Customer Requirements into Product Design (New York: Productivity Press, 1990), 17. ↵

- Gerson Tontini, “Deployment of Customer Needs in the QFD Using a Modified Kano Model,” Journal of the Academy of Business and Economics 2, no. 1 (2003). ↵

- Glen Mazur, “QFD for Small Business: A Shortcut through the Maze of Matrices” (paper presented at the Sixth Symposium on Quality Function Deployment, Novi, MI, June 1994). ↵

- David Carson, Stanley Cromie, Pauric McGowan, Jimmy Hill, Marketing and Entrepreneurship in Small and Midsize Enterprises (Hemel Hempstead, UK: Prentice-Hall, 1995), 108. ↵

- Malcolm Goodman, “The Pursuit of Value through Qualitative Market Research,” Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 2, no. 2 (1999): 111. ↵

- Shallee Fitzgerald, “It’s in the Cards,” Canadian Grocer 118, no. 10 (2004/2005): 30. ↵

- Jerry Katz and Richard Green, Entrepreneurial Small Business, 2nd ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2009), 17. ↵

- Alexander Hiam, Creativity (Amherst, MA: HRD Press, 1998), 6. ↵

- “Innovation Overload,” Trendwatching.com, accessed December 2, 2011, trendwatching.com/trends/pdf/2006_08_innovation_overload.pdf. ↵

- A. Roy Thurik, “Introduction: Innovation in Small Business,” Small Business Economics 8 (1996): 175. ↵

- L. Rausch, “Indicators of U.S. Small Business’s Role in R&D,” National Science Foundation (Info Brief NSF 10–304), March 2010. ↵

- Jancis Robinson, “The Oxford Companion to Wine,” 2nd ed., Wine Pros Archive, accessed October 8, 2011, www.winepros.com.au/jsp/cda/reference/oxford _entry.jsp?entry_id=430. ↵

- “Innovation Jubilation,” Trendwatching.com, accessed December 2, 2011, trendwatching.com/trends/innovationjubilation. ↵

- “Transparency Triumph,” Trendwatching.com, accessed December 2, 2011, trendwatching.com/trends/transparencytriumph. ↵

- MakinBacon, “Why and How to Identify Real Trends,” HubPages, accessed October 8, 2011, hubpages.com/hub/trendsanalysisforsuccess. ↵

- “Identifying and Understanding Trends in the Marketing Environment,” BrainMass, accessed June 1, 2012, http://www.brainmass.com/library/viewposting.php?posting_id=51965. ↵

- Rocky Fu, “10 Excellent Online Tools to Identify Trends,” Rocky FU Social Media & Digital Strategies, May 9, 2001, accessed October 8, 2011, www.rockyfu.com/blog/10-excellent-online-tools-to-identify-trends. ↵

The difference between the benefits a customer receives from a product or a service and the costs associated with obtaining the product or the service.

A basis of value that relates to a product’s or a service’s ability to perform its utilitarian purpose.

A basis of value that involves a sense of relationship with other groups by using images or symbols.

A basis of value that is derived from the ability to evoke an emotional or an affective response.

A basis of value that is generated by a sense of novelty or simple fun.

A basis of value that is derived from a particular context or a sociocultural setting.

A component that consists of the purchase, operating, service, switching, and opportunity costs associated with any product or service.

The time required to evaluate, acquire, and purchase a product or a service.

The element of cost that is associated with factors that might induce stress in a customer.

Dividing the market into several portions that are different from each other. It involves recognizing that the market at large is not homogeneous.

Any and all attempts to identify the real wants and needs of a customer.

A measure of the revenue generated by a customer, the cost generated for that particular customer, and the projected retention rate of that customer over his or her lifetime.

A value that discounts the value of future cash flows. It recognizes the time value of money.

An approach that takes the concept of the VOC seriously and uses it to help design new products and services or to improve existing ones. It takes the desires of consumers and explores how well the individual activities of the business are meeting those desires.

New ways in which a product or a service might be used, new ways of packaging a product or a service, or identifying new customers or new ways to reach customers.