Chapter 7 – Speaking or Signing Skills

Speaking and Signing Principles to Live By

Logan Fisher; Bibi Halima; and Keli Yerian

This chapter is about speaking and signing, so we will be discussing the presentational mode (productive skills) instead of the interpretive mode (receptive skills), but we will continue to talk about the interpersonal mode (interactive use of both productive and receptive skills). The principles in this chapter will help you do things like give speeches or tell stories in the case of presentational skills, and also how to maintain the flow of interaction in real-life conversations in the case of interpersonal skills.

Jump into it!

The first suggestion we have for you is to jump into using your language and embrace your mistakes. By pushing yourself to converse, even when you might not feel ready, your language skills will improve dramatically. As we talked about in Chapter 1, having perfect grammar or always remembering the right word for something is actually not required for communication. In fact, it’s the opposite! Communication itself is required to develop your grammar and build your vocabulary (not to mention culture and pragmatics). How do you do this? Well, if you’re trying to talk about something that happened yesterday but don’t remember the past tense, use the basic form of the verb that you do know and throw in ‘yesterday’ to compensate. If you’re learning a Sign language and don’t know a sign for a specific word, don’t be afraid to finger-spell it out! You will improve by pushing through the discomfort, and you will eventually get to the point where you can remember the past tense of the verb or the specific sign. Remember, practice is the key to proficiency.

Research Note

Research Note

In a study by Suryani and Argawati (2018), students in a language learning classroom completed questionnaires about their levels of risk-taking in language learning and also took a holistic speaking test about a general topic. The results showed that there was a strong 0.685 correlation between their risk-taking tendencies and their speaking abilities, revealing that the students who took more risks also had stronger speaking skills.

Seek out opportunities to practice

One of the benefits of living in the age of technology is that you don’t even have to leave your house to practice. There are many ways to practice with technology nowadays such as having short conversations about the weather with smart devices like Siri or Alexa. Or you can have longer interactions with generative AI technology. Beyond the comfort zone of smart technology you can branch out to chat with real people by using online apps, joining a local language circle, or finding friends that speak your target language. If you can find people, push yourself to have conversations with them in your target language! It might feel really awkward sometimes, but again, no matter if you’re talking to fellow learners or native speakers, embrace your mistakes! If that tip sounds familiar, it’s because these principles are so tightly related. Having a growth mindset means understanding the benefit of seeking out opportunities to push yourself out of your comfort zone.

Research note

Jin (2023) followed two groups of Korean students studying English as a foreign language. The control group received normal instruction while the test group participated in vlogging as a form of language practice. Data collected via questionnaires both before and after showed that vlogging decreased speaking anxiety and increased willingness to communicate, vocabulary, comprehension, fluency, and task-proficiency at a higher rate when compared to their control group counterparts.

Keep the conversation going

Once you’ve decided to find opportunities and just jump in, keeping the conversation going can be the next related challenge. It can be easy to give up and fall back to your first language if you get stuck, but there are plenty of ways to avoid this. Here are some ideas below for how to keep a conversation alive, both with smart technology and with real people. Many of these ideas will also show up in some form in the Strategies & Stories section of this chapter later on.

Here are some ideas

Keeping a conversation going can feel hard, but at the end of the day, it generates more practice in your target language, so go the extra mile to struggle through it! The practice will pay off.

Research note

Research note

Scholars from both cognitivist and constructivist perspectives believe that interaction is crucial for language learning. They believe that much of what is learned in a second language is learned through negotiation of meaning. In other words, learning is not limited to a one-way activity where students are passive recipients of knowledge from media or teachers. Instead, learners must also participate in the co-creation of meaning in interaction in order to more deeply acquire the language.

Communication can be messy

Use context, multimodality, and strategies such as circumlocution and translanguaging as much as you need to. Instead of being afraid that this is cheating, use these tools to your advantage! For example, if you don’t know the name of a color, point to it in the environment if you can. In this way you are using gesture (a form of multimodal communication) and your context to your advantage. You can also use little bits of another language you know to communicate an idea if the person you’re interacting with also knows that language. Translanguaging is a very natural way of communicating among multilingual people, so why not act like a multilingual person? That person might then be able to help you to learn that word in your target language.

If, however, you’re trying to maximize your practice using the target language, and find yourself falling back on your first language too much, you can try to use context and multimodality the most, as well as circumlocution. Circumlocution is another strategy that keeps you in your target language while you’re trying to express an idea you aren’t sure about. It consists of expressing a word in a roundabout way to compensate for not knowing or remembering specific vocabulary. For instance, if you don’t remember how to say yellow, you could say “banana color”. Or if you don’t know the word for motorcycle you can use “car with two wheels” (and mimic putting your hands on handlebars). Not only can this be helpful in your target language, you likely use circumlocution in your first language as well! In this case it is more likely to be for uncommon words, but the point stands that circumlocution is not exclusive to your target language.

Research note

A study on translanguaging by Ha et al. (2021) showed that using translanguaging wisely can increase learners’ confidence and fluency. This observational study was conducted with 70 students in a university English language class in the south of Vietnam. It shows that a translanguaging approach done with a trained instructor supported their learning and “contributed to a positive change in behavior, engagement, and motivation” (p. 338).

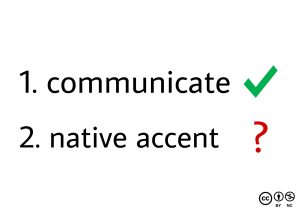

Embrace your accent

As you have heard us say so many times, focusing on perfection, whether grammatical or accent, can hinder effective communication. Moreover, when it comes to accent, variety exists in all languages, and as we discussed in Chapter 1 and Chapter 3, privileging native accents and other standard language ideologies often only functions to oppress people who speak differently. It is a fact that all languages have various native accents and there is no one correct accent in a language. Moreover, everyone has their own unique accent and idiolect anyway. If you have an accent that shows that you come from a particular place or that you have a specific first language, so what? You can be proud of where you come from and your accent can signal that you are a multilingual person. Of course, a certain level of accuracy in pronunciation is important so you’re not always being asked to repeat yourself. And you may have a personal goal of mastering the specific sounds of a language – this can be a very cool part of learning another language! The point here is to let your own interests drive your learning goals, not fear or shame about sounding different from people who grew up speaking the language.

Research Note

Research Note

The traditional goal of pushing learners to sound like “native speakers” has been recently widely criticized as being biased and unproductive for language learners and for social justice efforts in general. Holliday’s (2005) work, for example, traces how native-speakerism is an ideology that privileges standardized communities as true representatives of the language, when in fact a wide variety of speakers use the language in a multitude of different and valid ways.

Take time to notice what you don’t know

Although hopefully we have convinced you that perfection is not a realistic goal in actual language learning, you can definitely keep developing and improving your language skills! To do this, you need to keep noticing the patterns of the language, as well as the differences between how you are using the language and the way that more proficient speakers are using it. Noticing is a key ingredient for improving. At first you will only have the mental capacity to notice the basics of the language, but as you improve you will notice increasingly subtle things, including about languaculture. Little by little, you can keep adjusting your own version of learner language to approximate the versions of more proficient language users – that is, if you want to! Again, it’s all about awareness and choice regarding your own goals.

Research note

A study by Swain (1985) of French immersion programs in Canada showed that learners developed high levels of fluency but their grammatical accuracy was often compromised. This was attributed to the lack of focused instruction on accuracy within the immersion programs. The immersion environment provided many opportunities for fluency development, but without explicit correction and noticing forms such as grammatical elements or spelling, certain linguistic errors remained.

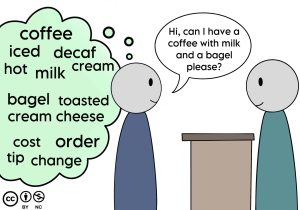

Learn relevant vocabulary

Another principle for making good progress in your language learning is to focus on vocabulary that is relevant to your life and interests. In other words, vocabulary that you will really use! Will you really need to ask things like ¿Donde está la biblioteca? (“Where is the library?”)? (If you took high school Spanish you know what we mean). Instead, if you can, try to focus on topics and situations that are important to you. For example, if you want to learn how to order at a restaurant, learn the names of specific dishes from your target language’s culture and how to say things like could I please, I would like, and do you have…? If you want to chat online about your passion for history on the other hand (or gaming or sports or fashion), your initial vocabulary might look drastically different! And remember, vocabulary includes verbs, the words that describe what you DO every day. Phrases like I want, I’m going to, I like, are all common things people say in languages worldwide. Focusing on common vocabulary, and on vocabulary that is important to you personally, can keep language learning relevant in your life and keep you excited to use your target language.

Research note

Scholars such as Nation (2022) and Vilkaitė-Lozdienė and Schmitt (2019) agree that learning high-frequency words, specifically the top 3000 most frequent word families, will facilitate spoken communication. These authors emphasize the importance of high-frequency words in achieving fluency and the ability to handle everyday conversations.

Be patient with yourself

Lastly, keep realistic expectations for yourself. Remember that language learning takes time, and the path to proficiency is not a steady progression that simply goes up and up. In fact, as we discussed in Chapter 1 most language learning is more like a meandering, spiraling path that goes up and down, with some breathtaking peaks, long valleys, flat plateaus, and slopes back downhill that make you feel like you are back where you started. But stay patient! The long valleys and plateaus are a natural and necessary stage of mentally solidifying what you have been learning (this inevitably hits you at the intermediate stage). The dips are a completely normal part of being tired, unfocused, or needing to take breaks in your learning when other things are going on. And, importantly, the peaks are amazing moments that can keep you inspired and help you see that you are indeed progressing. Being patient with yourself means letting go of the illusion of having complete control over your language learning progression. You have to just keep going and enjoy the ride.

References

Ha, T. T. T., Phan, T. T. N., & Anh, T. H. (2021). The Importance of translanguaging in improving fluency in speaking ability of non-English major sophomores. In 18th International Conference of the Asia Association of Computer-Assisted Language Learning (AsiaCALL–2-2021) (pp. 338-344). Atlantis Press.

Holliday, A. (2005). The struggle to teach English as an international language. Oxford University Press

Jin, S. (2023). Speaking proficiency and affective filter in EFL: Vlogging as a social media-integrated activity. British Journal of Educational Technology, 55(2), 586-604.

Nation, I. S. P. (2022). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge University Press.

Swain, M. (1985) Communicative competence: some roles of comprehensible input and comprehensible output in its development. In S. M. Gass and C. G. Madden (Eds.), Input in second language acquisition (pp. 235–253). Newbury House.

Suryani, L., & Argawati, N. O. (2018). Risk-taking and students’ speaking ability: Do they correlate? ELTIN Journal: Journal of English Language Teaching in Indonesia, 6(1), 34-45.

Vilkaitė-Lozdienė, L., & Schmitt, N. (2019). Frequency as a guide for vocabulary usefulness. In S. Webb (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of vocabulary studies (pp. 81-96). Routledge.

Media Attributions

All original illustrations on this page © Addy Orsi are licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 (Attribution NonCommercial) license.

Having the power of producing; generative; creative. In the context of language, creating output in the form of language

Having the quality of receiving, taking in, or admitting. In the context of language, taking in input in the form of language

The language you are currently learning

"a belief that intelligence can be strengthened and expanded through dedication and hard work" (Rasmussen, 2021).

A term used to describe a learner's probability of choosing to participate in the L2 of their own violation

A process of interaction in which speakers mutually negotiate their intended meaning using strategies such as clarification questions, repetition, and rephrasing to convey a clear message

Use of different modalities such as sight, hearing, or touching

“A communication strategy that allows language learners to express themselves even when there is a gap in their linguistic knowledge. This is achieved through using descriptions, explanations and definitions instead of the unknown target structure” (Worden, 2016).

The practice of mixing languages in a flexible way, either in speaking or writing

This refers to the L1 speakers of the language; however, we are problematizing this term because we do not want to imply that native speakers are always model speakers. See Chapter 1 for Nativespeakerism

"A bias toward an abstract, idealized homogenous language, which is imposed and maintained by dominant institutions" (Lippi-Green, 1997).

The particular way an individual speaks

The idea that a language is made up not only of its grammatical and vocabulary elements, but also past knowledge, inventions, cultural information, and behaviors that contribute to language change over time

The written or spoken language produced by a learner that reflects their own developmental stage of learning