Chapter 3 – Access and Power in Language Learning

Language Endangerment and Revitalization

Keli Yerian and Bibi Halima

PReview Questions

- What is language endangerment?

- Why are many indigenous languages endangered?

- What is involved in language revitalization?

- Why are language endangerment and revitalization relevant to language learning?

7164 languages!

According to Ethnologue, this is the number of living languages as of 2024 (Eberhard et al., 2024a). Does this number surprise you? It can be amazing to realize that there are over 7000 ways for humans to talk to one another. This means 7000 grammatical systems, 7000 systems for combining sounds or signs, 7000 inventories of vocabulary, and 7000 ways to express one’s culture and identity. And if we count languages from the past that are no longer spoken and the different varieties of languages that might be counted as the ‘same’ language, this number is even larger.

Languages at Risk

We may count over 7000 languages today, but this number is decreasing every year. Although language loss is not a new phenomenon, the pace of loss has accelerated in recent times far beyond historical trends, similar to the increasing pace of biodiversity loss. Ethnologue states that 42% of languages are currently at risk of disappearing from everyday use, which is a much higher percentage than in the past (Eberhard et al., 2024b). In other words, over 3000 languages are endangered right now and the rate of language endangerment is showing no signs of slowing down. Over half of today’s languages could be severely endangered by 2100 ( Sallabank & Austin, 2023).

UNESCO’s Atlas of World Languages in Danger categorizes endangered languages into six levels of risk, ranging from vulnerable to critically endangered or extinct (Moseley, 2010). Importantly, languages become endangered when they are highly minoritized. Through the processes of colonization and globalization, many minoritized communities have been forced or incentivized to adopt majority languages as their own.

Move the slider along the bottom of the image below to see this process in action in North America.

North American Language Groups from Pre-Colonization to Present

Move the slider to see change over time on the map below. Accessible description of the slider activity.

The disappearance of many indigenous languages in the Americas is a result of the suppression or active elimination of Native peoples and their voices. In the U.S. and Canada, children were forced to attend Boarding Schools that forbade them from speaking their own languages, which severed their linguistic and cultural ties to their original Tribes.

Before the arrival of European settlers in the 1600s, there were over 300 indigenous languages spoken in North America (Britannica, n.d.). Only around half of these have fluent speakers today, and it is estimated that without revitalization efforts, only around 20 spoken indigenous languages will remain in 2050 (Indigenous Language Institute, as cited by Cohen, 2010, in The New York Times). In the video below, Andrina Wekontash Smith, a Shinnecock educator, explains further about the history of indigenous language loss in the United States.

Are we losing more than words?

We may wonder, why does it matter to lose minoritized languages? We have the majority languages we can communicate in instead, right? Well, these questions are easiest to ask when your own language is not the one in danger. We may not always notice, but in each language lies the history of communities, the wisdom of collective minds and the incredible stories and ecological knowledge of human societies, in addition to a unique grammatical and sound system developed over thousands of years. It is in languages that we find diverse ways to express hope and dreams for our futures. People live through their languages!

Lost Words, Found Voices

At this point you might assume that once languages are lost, they are forever gone. But interestingly languages can come “back to life”. There are initiatives around the world led by community members, educators, linguists, and other scholars to document, reclaim and revitalize endangered languages. Some people are even reviving languages that have been considered “extinct” preferring to call them dormant or sleeping. These individuals and communities are putting tremendous effort into breathing life into ancestral stories and keeping traditional language in community daily life.

The process of revitalization involves “giving new life and vigor to a language that has been decreasing in use (or has ceased to be used altogether)” (Skutnabb-Kangas, 2018, p. 13). But it is not an easy or straightforward process. Reviving or maintaining the use of an endangered language usually involves multiple painstaking stages that depend on the status of the language in the community, the extent of documentation of the language, the number of resources and finances to support materials, community interest, and leadership.

This work can be slow and often painful. Elliott (2022) notes that, “language revitalization efforts are typically started by dedicated individuals or groups of individuals who aim to support their heritage language. In assembling a team, if possible, they start with the expertise of remaining L1 speakers, typically elders. They may choose to include on their team academics or experts, who may be either ‘outsiders’ or tribal members” (pp. 438-439). Examples of current revitalization efforts globally include the Ainu language in northern Japan, Quechua varieties in countries of the South American Andes, the Manchu language in China, and the Gunggari language in Australia, among many others.

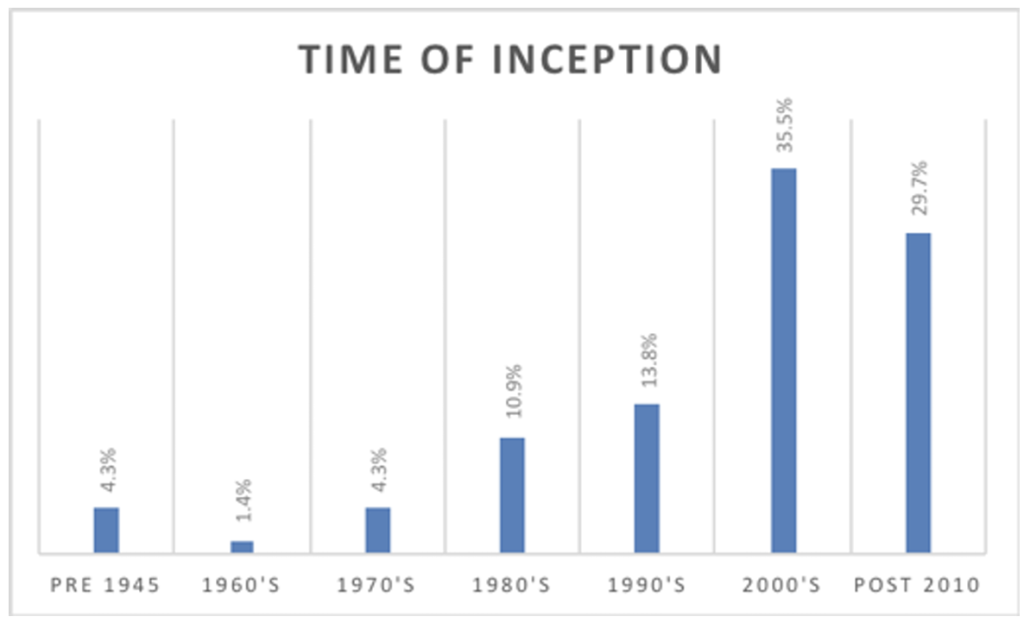

A worldwide survey shows that language revitalization efforts are a growing phenomenon globally. As shown in the graph below, more than half of these efforts began just within the last 25 years (Pérez-Báez et al., 2019). It is exciting to see that people of minoritized communities and their allies worldwide are raising their voices to sustain and empower their languages.

Revitalization Efforts In Oregon

If we zoom in on the Northwest United States we see many efforts underway. Below is a image hotspots map of some of the indigenous language revitalization projects currently happening in what is now the state of Oregon.

Image Hotspots map of Oregon Revitalization Efforts

Click on the green markers below to read information that has been published about these efforts. Accessible description of the image hotspots activity.

Institutes that support revitalization efforts allow for coordinated efforts in multiple communities. For example, the Northwest Indian Language Institute (NILI) was founded in 1998 in response to requests from Native communities of Oregon. NILI is situated in an “old white wooden house on the east edge of campus” at the University of Oregon and provides assistance for revitalization efforts in multiple indigenous languages including Ichishkíin, Chinuk Wawa, Tolowa-Dee-ni, and Lushootseed, among others (Elliott, 2022, p. 441). Their work includes teacher training, curriculum development, language documentation, appropriate uses in technology, outreach services on issues of language endangerment and advocacy for language revitalization issues (NILI).

What does this have to do with me?

You may be asking yourself this question. Our answer is threefold.

First, as we said in the previous sections on Heritage languages and LCTLs, for some of you this may be a very personal topic. if you are Native or have Native heritage, your own heritage language may be the one that you most want to learn.

Second, for those without a personal tie to an indigenous language, you still can participate in helping these languages thrive and prosper. Often classes at the university are open to anyone, no matter their heritage. For example in Eugene, Oregon, Ichishkíin is offered at the University of Oregon, and Chinuk Wawa is offered at Lane Community College. Taking a class on an indigenous language can give you insight and sensitivity to Native culture, history, and of course the language itself. The grammar of Ichishkiin, for example, is remarkably complex and quite different from most other languages. But learning in the classroom is not the only way. You can also participate in cultural events hosted on campus or in the community that celebrate indigenous peoples and languages. This can be a purposeful experience for those who want to explore a language different from the few majoritized languages typically offered worldwide.

Perhaps most importantly, whether or not you take an indigenous language class, by learning about endangered languages you will be more aware of the power and politics of language learning. You can become a strong advocate for supporting endangered minoritized languages and develop deep appreciation for the people who are learning and using them.

Pause and Explore

At the end of this section, assess your understanding.

Language Endangerment and Revitalization Comprehension Check

Select the best answer for each question.

References

Cohen, P. (2010, April 3). Indian tribes go in search of their lost languages. The New York Times. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

Eberhard, D. M., Simons, G. F., & Fennig, C. D. (Eds.). (2024a). How many languages are there in the world? Ethnologue: Languages of the World (27th ed.). SIL International. Online version: https://www.ethnologue.com/insights/how-many-languages/

Eberhard, D. M., Simons, G. F., & Fennig, C. D. (Eds.). (2024b). How many languages are endangered? Ethnologue: Languages of the World (27th ed.). SIL International. Online version: https://www.ethnologue.com/insights/how-many-languages-endangered/

Elliott, R. (2022). Language revitalization as a plurilingual endeavour. In E. Piccardo, A. Germain, & G. Lawrence (Eds.). The Routledge handbook of plurilingual language education (1st ed., pp. 435–448). Routledge.

Grenoble, L. A. (2013). Language revitalization. In R. Bayley, R. Cameron, & C. Lucas (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of sociolinguistics (pp. 792-811). Oxford University Press.

Hermes, M., Bang, M., & Marin, A. (2012). Designing indigenous language revitalization. Harvard Educational Review, 82(3), 381-402.

Moseley, C. (2010). Atlas of the world’s languages in danger. UNESCO. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

Pérez-Báez, G., Vogel, R., & Patolo. U. (2019). Global survey of revitalization efforts: A mixed methods approach to understanding language revitalization practices. Language Documentation & Conservation, 13, 446-513.

Reid, L. F., & Kawash, J. (2017). Let’s talk about power: How teacher use of power shapes relationships and learning. Papers on Postsecondary Learning and Teaching, 2, 34-41.

Sallabank, J., & Austin, P. (2023). Endangered languages. In L. Wei, Z. Hua, & J. Simpson (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of applied linguistics (2nd ed., Volume 2). Routledge.

Skutnabb-Kangas, T. (2018). Language rights and revitalization. In L. Hinton, L. Huss, & G. Roche (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of language revitalization (pp. 11-21). Routledge.

Image & Activity Descriptions

Language Groups Map Slides

Slide 1:

- Northern Canada, a few large language groups cover most of Canada:

- Eskimo-Aleut (The most Northern coasts and islands in North America)

- Na-Dene (North Western Canada and Alaska)

- Algic (extends into southern Canada and the Northern US, especially on the east coast of the US)

- South Western Canada and North Western US:

- Tsimshianic

- Wakashan

- Salishan

- Chimakuan

- Chinookan

- Plateau Penutian

- Cayuse

- A dense collection of smaller language groups along the West coast of the United States

- Kalapuyan

- Alsean

- Coosan

- Shastan

- Palaihnihan

- Wintuan

- Yuki-Wappo

- Pomoan

- Maiduan

- Utian

- Chumashan

- Yokutsan

- Salinan

- Esselen

- Washo

- Yana

- Chimariko

- Karuk

- Takelma

- Siuslaw

- Western and South Western US and North Western Mexico:

- Uto-Aztecan

- Yuman-Cochimi

- Seri

- Zuni

- Keresan

- Kiowa-Tanoan

- Caddoan

- Central and Mid-Western US, large language groups cover most of the central US.

- Siouan-Catawban

- Algic

- Kiowa-Tanoan

- Caddoan

- Southern US, along the Gulf of Mexico, small language groups.

- Tunica

- Natchez

- Chitmacha

- Adai

- Atakapa

- Karankawa

- Tonkawa

- Aranama

- Cotoname

- Coahuilteco

- Solano

- North Eastern US (inner New England and New york)

- Iroquoian.

- Near modern day Alabama: Muskogean.

- The Eastern and South Eastern US are largely unclassified and unknown on this map.

Slide 2:

Slide 3:

Slide 4:

Indigenous Language Revitalization Efforts in Oregon

1. The Chinook Nation

“The Chinook Indian Nation — whose ancestors lived along both shores of the lower Columbia River, as well as north and south along the Pacific Coast at the river’s mouth — continue to reside near traditional lands. Because of its nonrecognized status, the Chinook Indian Nation often faces challenges in its efforts to claim and control cultural heritage and its own history and to assert a right to place on the Columbia River. Chinook Resilience is a collaborative ethnography of how the Chinook Indian Nation, whose land and heritage are under assault, continues to move forward and remain culturally strong and resilient. Jon Daehnke focuses on Chinook participation in archaeological projects and sites of public history as well as the tribe’s role in the revitalization of canoe culture in the Pacific Northwest. This lived and embodied enactment of heritage, one steeped in reciprocity and protocol rather than documentation and preservation of material objects, offers a tribally relevant, forward-looking, and decolonized approach for the cultural resilience and survival of the Chinook Indian Nation, even in the face of federal nonrecognition” (Daehnke, 2017).

Reference:

Daehnke, J. D. (2017). Chinook resilience : Heritage and cultural revitalization on the lower Columbia River / Jon D. Daehnke ; foreword by Tony A. Johnson. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

2. Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians

The Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians is broadening language awareness by making a dictionary of Siletz Dee-Ni that is accessible to anyone.

“‘We don’t know where it’s going to go,’ said Bud Lane, a tribe member who has been working on the online Siletz Dee-ni Talking Dictionary for nearly seven years, and recorded almost all of its 10,000-odd audio entries himself. In its first years the dictionary was password protected, intended for tribe members.

Since February, however, when organizers began to publicize its existence, Web hits have spiked from places where languages related to Siletz are spoken, a broad area of the West on through Canada and into Alaska. That is the heartland of the Athabascan family of languages, which also includes Navajo. And there has been a flurry of interest from Web users in Italy, Switzerland and Poland, where the dark, rainy woods of the Pacific Northwest, at least in terms of language connections, might as well be the moon” (Johnson, 2012).

Reference:

Johnson, K. (2012, August 3). Tribe Revives Language on Verge of Extinction. The New York Times. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

3. Coquille Indian Tribe

“Creating programs to revive traditional languages among modern-day people is a challenge for any Indian Tribe. The Coquille Tribe has begun the project, and traditional words are slowly infusing Tribal programs and events. If you attend a Coquille event, don’t be surprised to be welcomed with the Miluk ‘Dai s’la!’ or the Upper Coquille ‘Jala!’,” (Coquille Indian Tribe, 2024).

Reference:

Coquille Indian Tribe. (2024). Living the Culture. Retrieved June 20, 2024, from www.coquilletribe.org/our-heritage/our-living-culture/

4. Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians

Patty Whereat Phillips and Enna Helms are implmenting a project that will help with reviltilization efforts for miluk, hanis and sha’yuushtɬ’a uɬ quuiich languages.

“Luckily, two Tribal linguists— Patty Whereat Phillips and Enna Helms— are paving the beginnings of language revitalization for three languages: miluk, hanis and sha’yuushtɬ’a uɬ quuiich. Together they lead four language classes taught to both Tribal members and college students on Zoom. Both women are active participants in Tribal committees, and Mrs. Helms is a Councilwoman on the Tribal Council. The Tribe needs are to build capacity in order to expand access to the language. We plan to supplement revitalization efforts with our proposed project of documentation, archival, and storytelling, capturing success and challenge stories.

This project effectively meets the Alumni TIES seminar theme shared ways of sharing underrepresented stories. By documenting experiences and creating a book, the Tribe’s history is preserved. It can help spread awareness about the Tribe’s history, values, and mythology and propel other stakeholders to join in on the cause. A book on traditional storytelling provides communities with diversity and representation, a desperately needed element for children’s books” (Fong, 2023).

Reference:

Fong, J. (2023). Documenting Language Revitalization & Storybook. MIT SOLVE. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

5. Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

A language revitilization effort by the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde began in 2000. It was a language immersion program that intergrated their language into the community to help with revitltization efforts.

“For the past dozen-or-so years, the Confederated Tribes of Grande Ronde, just an hour north of Corvallis, have made intensive efforts to revitalize Chinook Jargon—or, as they call it, Chinuk Wawa—through childhood immersion programs and adult literacy classes” (Brodie, 2012).

Reference:

Brodie, N. (2012, December 13). Chinuk Wawa: A Local Oregon Tribe’s Efforts to Save a Dying Language. The Corvallis Advocate. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

6. Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Indians

The Takelma language, once spoken by the Cow Creek Band of the Umpqua Tribe of Indians and others, went extinct in Southwestern Oregon by 1940. Now, tribal members are in the process of reviving it.

“The ancient Takelma language had been spoken at least since Europeans first arrived, according to Dr. Stephen Beckham, retired Pamplin Professor of History at Lewis & Clark College. The language disappeared over time as tribal members were removed onto English-speaking-only reservations.

Now, tribal members are in the process of restoring it.

At 21 years old, tribal member Elizabeth Bryant is the most fluent speaker of the language. She’s the Lead Takelma Teacher Learner for the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians. And for the past three years, she and a few others have been working on creating a dictionary and teaching classes to tribal members. The goal is to revitalize important history.

“It really ties into that sense of my ancestors. And this is where I come from, these are my people who are no longer with us. And so it’s very much an emotional connection to what they could have been thinking,” she said.

In 2019, the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians received a three-year grant from the federal Administration for Native Americans to do this restoration work. They hired Curriculum Specialist and Applied Linguist Dave Prine to help” (Vaughan, 2022).

Reference:

Vaughan, J. (2022, November 25). Cow Creek Tribe Works to Restore Once-Extinct Language. OPB. Retrieved June 20, 2024, from www.opb.org/article/2022/11/25/cow-creek-tribe-southern-oregon-works-to-restore-once-extinct-language/

7. Klamath Tribes

Early Childhood Klamath Language Immersion Program

“In an effort to preserve their native language, the Klamath Tribes has introduced an early childhood language immersion program teaching Klamath to children at the tribes’ Early Childhood Development Center (ECDC) in Chiloquin. Revitalizing indigenous languages is an ongoing effort by tribes across the country, and for children to best succeed, lessons should begin at an early age.

The ultimate goal is to develop a generation of fluent Klamath speakers who can then teach their children the language. With only a handful of tribal members who are master speakers, the challenge is all the greater to teach a new generation of fluent Klamath speakers” (Smith, 2023).

Reference:

Smith, K. (2023, June 1). Early Childhood Klamath Language Immersion Program Educates Next Generation of Speakers. Herald and News. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

8. Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs

“The Language Program offers several programs such as:

- Rise and Shine at Warm Springs K-8 Academy – all languages and College Success, Rites of Passage

- Immersion at Warm Springs K-8 Academy – Ichishkin language

- Ichishkin at Culture & Heritage by Suzie – MW nights

- Kiksht at COCC – Credit Classes at COCC Madras

- Autni Ichishkin Sapsikwat at Warm Springs Daycare – Ichishkiin Language”

Reference:

Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs. (2021). Language Program. Retrieved June 20, 2024, from warmsprings-nsn.gov/program/language-program/

9. Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation

There has been a lot of collaboration between the Northwest Indian Language Institute at the University of Oregon and the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (CTUIR). Below is a description of one of the language revitilization efforts that has been a combined effort of NILI and the CTUIR.

“Over the years, NILI and CTUIR have collaborated on numerous projects. A recent example is the eBook project. NILI faculty collaborated with teachers and students at Nixyaawii Community School, their Tribal high school, to create multimedia materials in one of the indigenous languages that the small children in the immersion preschool could use. Over a period of two years, multiple trips were made to CTUIR, a small library of eBooks were developed, and several Nixyaawii youth took part in NILI Summer Institute. The team, including several Nixyaawii students, traveled to national conferences, such as the National Indian Education Association conferences in Alaska and Portland, where they presented on the project,” (Northwest Indian Language Institute, 2024).

Reference:

Northwest Indian Language Institute. (2024). The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation. Retrieved June 20, 2024, from nili.uoregon.edu/umatilla-2/

10. Burns Paiute of Harney County

A grant was offered to the Burns Paiute of Harney County was offered a grant of $6,345 in the year 2024 for language revitalization efforts.

“The Burns Paiute Tribal Council has approved funds to be used for the Wadatika Neme Yaduan Nobi, a tribal language and traditional culture revitalization effort,” (Oregon Cultural Trust, 2024).

Reference:

Oregon Cultural Trust. (2024). Cultural Coalitions: Burns Paiute Tribe. Retrieved June 20, 2024, from www.culturaltrust.org/about-us/coalitions/burns-paiute-tribe/

Media Attributions

- time-of-inception