16 Napster, the iPod, and Streaming: The Record Industry in the New Millennium

Without a doubt, the big story of the new millennium has been the collapse of recorded music sales due to MP3 piracy and the subsequent recovery fueled first by Apple’s iTunes and now streaming. The big non-story is the continued consolidation of the record industry into three major companies that dominate the industry globally. Let’s start with the rise of Napster and MP3 piracy.

Recorded music piracy did not begin with MP3 files. There were previous underground markets for bootleg vinyl records, then a bigger market for easier-to-create bootleg cassette tapes, and then bootleg CDs. However, MP3 piracy became an industry-wide threat in the 1990s primarily for three reasons: (a) the advent of peer-to-peer (P2P) file networks and software that accompanied widespread availability of high-bandwidth internet, (b) a pervasive sense of entitlement to free music among consumers driven by a lack of respect for the record industry, and (c) the record industry burying its head in the sand rather than quickly moving into the internet age.

When 19-year-old college student Shawn Fanning started Napster in June, 1999, it was not the only peer-to-peer file-sharing network on the internet. But it was the easiest to use and Fanning marketed it successfully to young music consumers. So, it became the public face and name for both fans and critics of peer-to-peer technology. By downloading the free Napster software to their computers, users could put links to MP3 files that they had ripped from CDs onto Napster’s index, allowing other users to search for songs (or other media files) and download them directly from the computer of the user who had listed them. This is an important point about P2P networks: the files themselves were not stored on central P2P host servers. Napster and other P2P networks only offered indexes of links to files stored on users’ computers, thus the name of the technology — “peer to peer”. This will become an important legal distinction as we move forward in this story.

Within a year of its release in 1999, Napster had over 100,000 users whose primary activity using the program was freely sharing, rather than purchasing, copyrighted music. The threat to the recording industry was so obvious and ominous that the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), whose mission it is to promote and protect the recording industry, filed suit in federal court against Napster, alleging massive copyright infringement. However, the publicity and sense of entitled anger at the “greedy” record industry only served to increase Napster’s popularity among college-aged youth, who took advantage of high-speed internet on college campuses to increase their use of the service. The global consolidation of the record industry discussed above, as well as the elevated price of CDs, helped fuel a sense among young consumers that the industry deserved what they were getting. The sense of youthful rebellion, combined with a “revenge of the nerds” narrative of clever computer coders disrupting the world, fueled a narrative that “music should be free.”

Seemingly lost in this mass youth rebellion against the industry was the fact that young musicians were just as likely as the “evil” record companies to suffer from music piracy. But musicians became the sacrificial lambs in this equation, a scenario no doubt fueled by the lingering Romantic idea of musicians not being in it for the money anyway. The alienation of musicians only increased when heavy-metal band Metallica and hip hop producer Dr. Dre joined in the fray with their own lawsuits against Napster in 2000. Napster settled out-of-court with Metallica and Dr. Dre, but the RIAA’s lawsuit advanced to the point that Napster was ordered by the court to keep track of all downloads of copyrighted songs and their points of origin. Unable to comply with the court order, Napster shut down their service in July, 2001, after only two years of operation.

Napster’s demise, however, did nothing to stem the tide of P2P file sharing, as other similar companies rushed in to fill the void, such as Kazaa, Gnutella, and Grokster. Unable to stem the tide of online MP3 piracy, the record industry made a fatefully ill-considered decision: rather than working to embrace and compete in internet music distribution, it decided to double-down by going after individuals who were sharing music on the P2P networks, filing 261 lawsuits against P2P users in 2003. In the first such case to go to a jury trial, a single mother in suburban Minnesota was held liable for $1.5 million in damages for sharing 24 songs online. (The damages award was so high because the damages were calculated not by the number of songs, but the number of downloads of those songs.) The resulting publicity from this and other cases was disastrous for the record industry, reinforcing the image of an industry doing anything to protect its profits and nothing to embrace the new technology.

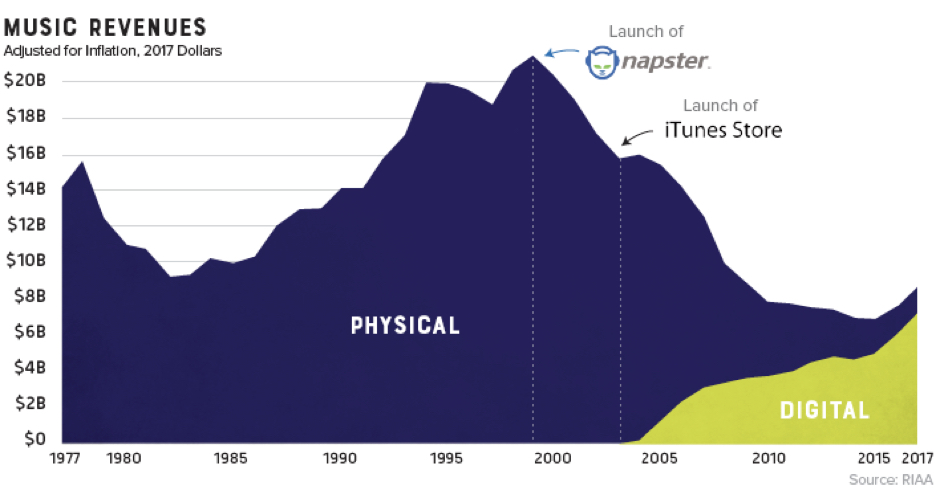

The use of P2P networks to share copyrighted music continued to rise, and the damage to the industry was becoming clear: CD sales were down over 10% in 2002 and the declining trend continued nearly unabated until 2015. By 2015, recording industry revenues had declined to less than half of their pre-Napster levels! (It is difficult to factually attribute all of this decline to P2P file sharing, as there are numerous variables involved, but the correlation is clearly well beyond coincidental.)

The record industry did attempt in the late 1990s and early 2000s to sell music downloads on the internet to compete with the P2P piracy networks, but those efforts failed to gain traction with consumers due to high prices and policies that limited the duration and use of a downloaded file. The first such service, opened in 1998, required consumers to burn a CD from their downloaded file in order to listen to it. However, portable MP3 players had already become widely available by that time so consumers predictably viewed that as antiquated and inconvenient, if not insulting. Another industry-wide effort backed by Sony sold downloads for $3.50 per song for a file that expired after a certain duration requiring repurchase. These efforts failed to convince young consumers to abandon the concept of free music downloads using P2P internet services.

The record industry’s inability to successfully transition to a sanctioned and attractive internet-based distribution of recorded music created an opportunity for another industry to fill that void. So, right on cue, Apple Computer stepped up to seize the opportunity, pulling the rug out from underneath the record industry and changing the industry’s entire business model within just a few years. Apple introduced the iPod MP3 player and its accompanying iTunes on-line music store in 2003. By 2011, Apple had sold 300 million iPods and 10 billion songs through iTunes. But that represented less than 10% of Apple’s total revenue during that period. Apple has continuously used music as a point of entry into its more lucrative phone and computer hardware sales, rather than as a profit center. Unlike a record company, music sales represent only a way for Apple to attract customers, rather than the main source of revenue. This allows Apple to compete on price in a way the record industry never could. Consequently, Apple was happy to sell songs at $0.99 for each download rather than pushing consumers to purchase whole “albums” of songs for $15, which was still the record industry model. Given the depressed state of CD sales from MP3 piracy, the record industry was in no position to refuse Apple the licenses to sell their music in this way (particularly as Apple had developed a secure rights-management system to ensure that their files could not be shared). Apple’s online iTunes store quickly became the highest-grossing music retail outlet in the United States, hastening the demise of brick-and-mortar record stores. The largest and most iconic of those stores, Tower Records, declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2004 and again in 2006, followed shortly that same year with complete liquidation of the company’s assets. In just a few years, iTunes had complete destroyed the traditional retail music sales industry. (Not coincidentally, Amazon had previously done the same thing to the book publishing industry, which also was too late to compete with Amazon’s online and electronic book sales before the retail bookselling industry was eviscerated.)

While the success of iTunes and legal MP3 downloads translated as a positive development for Apple, that was not the case for the record industry as a whole. It wasn’t until 2015 that the record industry turned the corner and began to recover from the disasters of the previous two decades. The engine that fueled the recovery was not the sales of downloaded songs, however — it was an even more disruptive technology, music streaming. Music streaming comes in two flavors that are important to keep conceptually separate — interactive streaming and non-interactive streaming. The difference is relatively simple: Interactive streaming involves the consumer choosing which song to listen to, while non-interactive streaming involves the streaming company choosing which song to offer the customer (typically contained within a station or curated playlist). As we will see later in the chapter on copyright royalties, this difference is important in determining how much artists and songwriters get paid.

The first big streaming success came with Pandora, a non-interactive streaming site offering internet radio through its website and mobile app. Pandora curates its streams based on a customer’s listening history and feedback, but the user does not search and choose which songs to stream (which makes Pandora non-interactive service). Pandora was founded in 2000 but did not gain traction with the public until roughly 2010, when it had 45 million users. By 2012, that number had grown to 125 million and in 2011 the company began offering its stock to the public. Like traditional “terrestrial” radio and most internet services, Pandora’s revenue is based largely on advertising played to users in between songs. Like many internet services, however, Pandora was plagued by the structural limitations of its free-use advertising-based business model — steadily increasing revenues, but negative net-income (i.e., no profit). The costs associated with licensing the music to provide to customers always exceeded the ad-based revenue — in other words, the business model does not “scale”, so growth is always accompanied by costs that exceed the increase in revenue. By 2018, Pandora realized its business model would never turn a profit, so it agreed to be purchased by satellite radio survivor, SiriusXM (itself the product a merger of the two pioneering satellite radio providers, Sirius and XM) for roughly $3 billion. Interesting, isn’t it, that a company that had never turned a profit could be worth $3 billion? The value was apparently in was is known as the company’s “goodwill,” that is its name, customer base, relationships, and potential.

Pandora’s inability to translate its success with users into profits was also partly due to the simultaneous rise of interactive streaming and its primary innovator, Swedish company Spotify, founded in 2006. Interactive streaming offers consumers the opportunity to choose their own music (what a concept!), so it has been able to accomplish what Pandora never could — get most users to agree to pay a monthly subscription fee rather than relying on advertising revenue. Pandora never managed to get more than about 20% of its users to convert from free, ad-supported memberships, to its premium ad-free membership that required a monthly fee. Spotify, however, has been able to achieve a nearly 50% subscription rate among its users as of 2020. Subscription fees translate into not only increasing revenue but higher net-income (profit) because such fees create regular, guaranteed income, even from users who don’t actually use the service frequently. Most critically, that translates into lower music licensing fees per user. However, even Spotify has itself trouble turning profits, with only one profitable quarter (4th quarter of 2018) since it went public in the spring of 2018 (companies do not have to report earnings unless their stock is publicly traded).

Spotify is not the only interactive streaming site, of course, so another major problem for the company is competition. Apple Computer has now become Spotify’s primary competitor, and again the problem for Spotify is that Apple does not rely on revenue from its new streaming service (Apple Music) to fuel its profits. Apple, which earned profits of over $55 billion in 2019, can afford to run its music streaming service at a loss in order to achieve its real purpose, which is to drive customers to its hardware products, particularly the iPhone. Apple’s ability to compete with Spotify and other streaming services on price, but without worrying about profits for that service, poses a significant challenge to the music streaming business model.

It is worth noting that Apple’s formula for success, using the sale of media content to drive the more profitable sale of hardware, is the business model that was used successfully by the record industry in its first decades before the Great Recession. Victor Records, Edison, and Gramophone all made music record players as well as the records and cylinders consumers played on those devices. The higher-margin sales of the hardware supported the less profitable business of making and selling recordings. No doubt many record company executives currently wish that model had not been abandoned by the record industry when it rebuilt itself after the Great Depression.