Learning Theories

Learning Objective

- I can understand and explain the difference between behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism.

There are many different learning theories, but let’s talk about three very influential ones: behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism. You’ve likely had run-ins with these but been unable to identify them. “Why is it important to identify them?” You might ask. Since many people have different ways and preferences for learning, these theories can help us understand what we are doing when we learn. The things that build long-term recollection of vocabulary for one person might not work for another. If you want to continue teaching yourself languages, diving into learning theories is imperative to optimize your knowledge of not only your target language but also how you learn in general.

Behaviorism

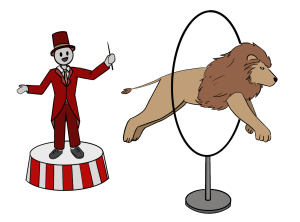

Behaviorism explains learning by saying, “People need to be directed and […] if the stimulus is something that the individual wants (a reward) or fears (a punishment), then the individual will respond accordingly and there will be a noticeable change in behaviour” (Bates, 2016). This means that you are training your brain like a ringmaster trains a lion to do tricks in the circus. Much like the lion and the ringmaster, behaviorism relies on providing a specific response to a specific stimulus and the consequential reward to indicate correct behavioral patterns.

Language apps like Duolingo are an amazing example of behaviorist learning. Each time you get an answer right, you are rewarded with a *ding*. Whether you realize it or not, that ding (positive reinforcement/reward) makes your brain feel happy because it releases serotonin – the positive reinforcement for your correct response. At the end of the lesson, you are rewarded yet again with experience points, which in turn means the release of more serotonin. Your brain is being rewarded for regurgitating information it doesn’t necessarily know how to use in context. This “gamification” of language learning is not bad. Still, learners may overestimate their skills because of that serotonin release, thinking that mastery can be achieved on an app.

Let’s put this concept into context. Let’s do a miniature language lesson, and since I’ve been harping on common language learning apps so much, I’ll format this lesson like theirs. You will see flashcards in Punjabi that relate to activities later in this section, and it is your job to remember words solely by seeing them and their translation. You may spend as much time as you want studying the cards, but once you move on to the video, don’t go back to the flashcards. I want you to notice what you learn. Maybe how much, or how little. How difficult was it? Maybe you know how to say certain phrases, but can you put them in context?

Though you may have done well and perhaps even memorized all the vocabulary, remember that the validation you receive is not always indicative of your skill to actually use the language in real life.

Cognitivism

Cognitivism is a vastly different learning theory from behaviorism. It acknowledges that “information is actively processed inside the mind of the person and the behaviour modification takes place by searching for the relationships that exist between the various bits of information. ” (Bates, 2016). Instead of the regurgitation of knowledge that occurs in behaviorism, there is more active engagement of the learner’s brain than we see in behaviorist tasks. Cognitivist learning can look like the solving of language puzzles, the analysis of scripted dialogues, and more since these activities encourage our brains to search for relationships in the material.

Cognitivism sees the active engagement of the learner and the creation of new ideas built on class material through drawing on our schemata – our prior knowledge. Through analyzing written or spoken dialogues, for example, you might be able to guess at some phrases right away – things like ‘Hello’, and ‘My name is’ based on your knowledge of body language or how greetings typically work. In a crossword in your second language, you may use your knowledge of your first language and word play to figure out a clue. Using your brain to form more long-term connections and pattern recognition leads to better retention and understanding of knowledge.

For our activity this session, we won’t be actively engaging in the conversation, but we’ll be watching a scripted conversation happen. Abhay and Halima are two of my colleagues who also wrote this book, and they also happen to both speak Punjabi. There will be subtitles in Punjabi and romanized Punjabi, so feel free to follow along out loud. Throughout this activity, you might struggle to understand what Abhay and Halima are saying unless you speak Punjabi. If you don’t speak Punjabi, let’s see how you can use your brain to try to make sense of what is happening in this next video, using the Punjabi words you have already learned in the previous flash-card activity, your own powers of observation, reasoning, and inferences based on your own lived experiences.

Abhay and Halima video

How do you feel after this activity? Confused? Overwhelmed? Interested? Maybe you are excited that you picked up a few words or pleased that you could infer that they were greeting each other without knowing all the vocabulary. All of these are completely normal reactions. As mentioned above, cognitivism is a theory that says learners need to do this mental work, to “search for the relationships that exist between the various bits of information (Bates, 2016)”. We can’t just memorize information; we need to puzzle through it actively. Cognitivism is missing something that the third theory, constructivism, has, however: learning through social interaction. The next section shows what happens when we blend our own understanding of ideas with the ideas of other people, pulling from our communal lived experiences to create new thoughts and sentences.

Constructivism

Constructivism is a theory that stresses how learners actively build their own understanding instead of passively receiving information, emphasizing on the role of experience, interaction, and reflection in the learning process. It is important to note that constructivism unlike cognitivism, does not separate learners’ mental process from their learning experience but highlights that “… the individuals’ contributions to what is learned are not negligible and the culture and social environments in which individuals interact with others are also important in acquisition of skills and knowledge” (Baştürk, 2016, p. 904). This essentially means that according to a constructivist approach, the social environment in which learning occurs is quintessential to forming a learners knowledge rather than the internal learning seen in cognitivism. Whereas a teacher who is influenced mostly by cognitivist theories might be happy to just lecture in front of the classroom and give homework for students to practice individually, a teacher inspired by constructivist ideologies would emphasize student-led activities, questions, projects, and anything that helps the students learn together. For our last activity in this section, we can’t fully embody constructivism in this book since you are likely reading it on your own. Instead, we’ll go through some exercises to imagine what constructivism could look like in practice. Let’s keep going with our Punjabi example and imagine each of the following examples of constructivism in practice.

- Travelling to Pakistan or India where Punjabi is spoken and learning by practicing with local speakers

- Finding a South Asian culture club near you and finding people with whom to practice Punjabi

- Going on language learning social media apps and finding Punjabi speakers

Furthermore, outside of the Punjabi specific examples, constructivism can look like…

- Exploring shopping sites in your target language with a study buddy

- Going to a restaurant of your target language’s culture with friends and speaking in your target language the whole time

- Describing an image to your peer who cannot see it and have them guess it

- Creating an original dialogue with a peer in a language class

Reflecting on our past language learning

Now that we know about and have practiced and imagined learning a language with a focus on three main learning theories, sit down and ask yourself the questions that we started with. How have you been learning languages in the past? Has it been effective? What works and doesn’t work for you? Your ideal learning situation may be unique and different from everyone else’s on the planet, so the beauty of independent language study, whether you are taking a language class or not, is that you get to create your own environment. Learning is also not a one-size-fits-all solution. Your possible ideal environment could incorporate varying degrees of behaviorism, cognitivism, and constructivism. Notice that these three theories can all help describe different aspects of language learning, and they can even build on one another, as we saw above. With a better awareness of how learning works in our brains, we can expand our learning cycles to see the possibilities of learning more effectively. Maybe you use Duolingo for 15 minutes a day to review and learn vocabulary, you watch one episode of your favorite show in your target language, and you speak with your more fluent friend for 20 minutes. Maybe it’s best to not close ourselves off to one idea of language learning as the ‘best method’, but perhaps a combination of all of these is best. Ultimately, that’s up to you to decide for yourself.

The use of game like thinking and game like mechanics in non-game situations, typically to engage users

The latin based writing of a language that doesn't use a latin alphabet