3b. Developing Questions at Issue

Question at Issue (Q@I)

The type of argument we practice at UO is known as ethical argumentation, or argumentation for the sake of inquiry. Inquiry is the act of asking questions, of investigating an issue or problem. We teach this type of argumentation at the college level because asking questions is exactly what you’re asked to do in your other classes; the modern American university is premised on the idea that its graduates will take the tools and knowledge they gain in their studies and go out into the world to help solve complex problems facing society.

Therefore, we teach argumentative writing that attempts to answer a controversial or debatable question, which is known as a question at issue (or Q@I). A question is at issue when the audience is not in agreement about the answer, so the writer must offer a reasonable answer and support that answer with evidence.

This is an example of a question that is NOT at Issue:

Was the United States founded in 1776?

This question is not at issue because there’s no reasonable debate about the answer. Reasonable people–from expert historians to the average person on the street–would agree that “yes” is the only valid answer to that question. An unreasonable person might want to debate that, but there’s not much point engaging in reasonable debate with an unreasonable person (though we’ve all had to do it occasionally).

This is an example of a question that IS at issue on a similar topic:

Did the founding of the US improve living conditions for most people living in the colonies?

Even if you’re not a US historian, you can imagine that there might be some reasonable debate about the answer to this question. Some people might assume the answer is “yes,” some might assume the answer is “no,” while still others could argue the more cautious position of “it depends.” But even those that agree that the answer is “it depends” might disagree on what the answer actually depends on. And importantly, there can be a reasonable debate on all of those positions backed up by evidence: tax records, first-hand accounts, information about slave auctions, etc.

Understand the difference?

Image by Arek Socha from Pixabay

Finding good Q@Is is not always an easy task, and depends on your own critical and methodical reading, careful attention to class conversation, and consideration of your own assumptions and experiences in relation to the topic at hand.

You will know you’ve identified a good question at issue (Q@I) for your class when:

- Disagreement exists about the answer or possible answers to the Q@I.

- It’s an issue that the discourse community cares about (meaning that it’s related to class readings and discussions).

- You care about this issue and question.

- It’s specific enough to answer persuasively in the space allotted for the essay.

- The question calls for logical, evidence-based support, and stakeholders within the discourse community are capable of being reasonable about the issue.

- It’s the type of question you want to pose.

In WR 121, Q@Is should be formulated as controversial, specific, yes/no questions. To generate yes/no questions (also known as “divided” responses), pay attention to the language used:

- “Multiple response” questions tend to start with words like who, what, why, and how. These types of Q@Is will be covered in WR 122/123 because they often require much longer answers, which translate to longer essays than what we require in WR 121.

- “Divided response” questions use words like is, are, can, will, do, does, would, and should

Yes no hands by cottonbro on Pexels.

When considering whether or not your Q@I is arguable, consider the following:

- Does the question demand a clear stance? Can your peers quickly take a stand one way or the other?

- Is there reasonable disagreement about the answer to the question? Is it possible that your audience could be persuaded to agree to your answer to the question?

- Does your question use debatable, specific words, like “best,” “worst,” “most,” “least,” or “better”?

- Does your question at issue relate to the readings and discussions of the class?

Remember: While many questions will occur to you, identifying a question does not necessarily mean you’re identifying a Q@I. Which of the following questions are NOT effective Q@Is?

Is college good for people to attend?

- Not a question at issue. The use of “good” here makes the question much too vague and broad, so there can’t be reasonable, evidence-based debate on the answer to the question.

Should universities pay foreign language teachers more so that we could see if it would increase the quality of foreign language education?

- Not a question at issue. But this is a tricky one. The problem here is not one of specificity, but rather that it’s asking two questions, not one: (1) Should universities pay foreign language teachers more? AND (2) would paying foreign language teachers more increase the quality of the language education? In truth, either one of those questions alone would be a good starting point for a Q@I, but together they’re not focused enough to have a reasonable debate in the space allotted for our essays.

Would spending more time on grammar instruction in college writing courses produce college graduates with better writing skills?

- This question is at issue. It’s debatable, specific, and answering it persuasively would require logic and evidence. It’s asking a type of question known as a “Question of Consequence.” Framing your question at issue as a type of stasis question can help you find a good question at issue more quickly. For more on Stasis Question Types, click “Next” below.

Types of Questions at Issue: Stasis Questions

How do you know a question is a good question?

- Disagreement exists about the answer or possible answers to the question

- It’s on an issue that the discourse community cares about (meaning that it’s related to class readings and discussions)

- You care about this issue and question

- It’s specific enough to answer persuasively in the space allotted for the essay

- The question calls for logical, evidence-based support, and stakeholders within the discourse community are capable of being reasonable about the issue

- It’s the type of question you want to pose

Stasis Questions are types of questions that can help you to find more specific, debatable Q@Is.

Some stasis questions lead to better questions at issue than others. For example, questions of fact can be controversial (meaning that people debate the answer), but it depends on the subject. The concept of Stasis Theory was originally developed by the ancient Greek philosophers Aristotle and Hermagores and further enhanced by the contributions of Roman and many later rhetoricians.

Stasis is hitting on that point in an issue where people will have different points of view. Have you found stasis with the question you want to write on? Ask yourself:

-

- Is it provocative and arguable?

- Is it framed as a yes/no question?

- Is it specific enough to be answered persuasively (with the evidence available!) in an essay of at least [insert minimum word count here]?

In The Shape of Reason (1986), John Gage develops six types of stasis questions that are useful for creating your own questions at issue or identifying questions at issue (aka main ideas) in sources you are reading. Our definitions and examples of these questions are adapted from The Shape of Reason and the pamphlet Reading, Reasoning, and Writing (2015) by Jim Crosswhite.

Knowing the type of Q@I you are asking is important. It tells you the kind of work you need to do in your essay and helps determine the argument you’ll need to make to answer it. For example, A question of policy (Should we ban smoking on campus?) requires a different argument than a question of consequence (Would banning smoking on campus reduce litter on campus?)

Questions of Fact

These depend on whether something is true, does exist, or has happened. In many cases, as with journalistic or scientific questions, proving these answers might only require looking something up in a textbook or other reliable source. As such, they tend not to be “at issue” as often.

Examples: Are there 24 hours in a day? Do bears hibernate?

Image: Grizzly bear by Gregory Smith is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 license via Wikimedia Commons

Questions of Definition

These questions depend on the specific definition of a word or phrase. A definition might be as simple as looking something up in a dictionary, or comparing the meanings that differ between sources.

Examples: Is flag-burning illegal? Can an exotic animal be a pet?

Image: Tiger King by Trusted Reviews is licensed CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Questions of Interpretation

These types of questions depend on how an author interprets a word or phrase that is not as simple as a dictionary definition. It might also seek an explanation of something’s significance. They often require authors to articulate or defend their point of view.

Examples: Is Batman a true hero? Are mandatory minimum sentences necessary?

Image: Batman; 20th Century Studios, CC0

Questions of Value

Value questions add shades of good/bad or right/wrong to a question of interpretation. In these cases, the positive or negative connotations of the language signal the underlying value. Questions of value and Questions of interpretation are very similar types of questions and often result in similar types of arguments.

Examples: Are Disney movies sexist? Is it wrong to ban books?

Image: Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Four Color Comic by Tom Simpson, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Questions of Consequence

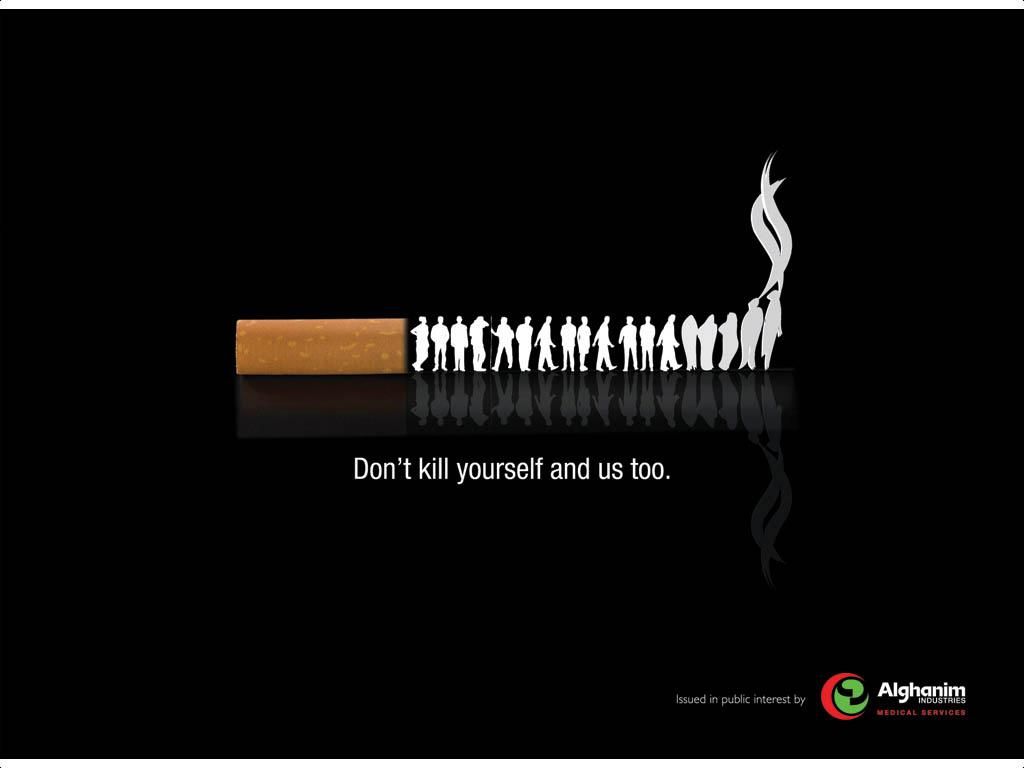

Questions like this deal with cause and effect: If X happens or is true, will Y follow as a result? The best examples of these questions avoid vague verbs like change, affect, and influence, and try to use descriptive or “directional” verbs that add information and make a debate more likely.

Examples: Do anti-smoking campaigns discourage teens from trying cigarettes? Do gender-specific summer camps promote healthier self-images among young girls?

Image: Anti-smoking PSA from Alghanim Industries

Questions of Policy

Policy questions occur when a discourse community might agree on every other aspect of a topic, but the question of “What should we do about it?” is the point that divides them.

Examples: Should the government lower the legal drinking age? Should schools require students to say the Pledge of Allegiance?

Image: Students pledging allegiance; US Department of Agriculture, CC0

Brainstorming

1. Make a list of as many questions you can on an issue you want to address or your essay topic

- What types of questions are you asking? What other types of questions are worth asking?

2. Turn these into yes/no stasis questions:

- What questions spark the most interesting debate to you?

Acknowledgments:

The six types of stasis questions identified in Chapter 3b are adapted from pages xviii-xix of “Reading, Reasoning, and Writing about Science,” by James Crosswhite from The Culture of Science, 2nd Edition (2019) by University of Oregon Composition Program, which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.