2a. Critical Reading

An Introduction to Reading in College

While the best way to develop your skills as a writer is to actually practice by writing, practicing critical reading skills is crucial to becoming a better college writer. Careful and skilled readers develop a stronger understanding of topics, learn to better anticipate the needs of the audience, and pick up sophisticated writing “maneuvers” and strategies from professional writing. A good reading practice requires reading text and context, which you’ll learn more about in the next section. Writing a successful academic essay also begins with critical reading as you explore ideas and consider how to make use of sources to provide support for your writing.

Questions to ask as you read

If you consider yourself a particularly strong reader or want to improve your reading comprehension skills, writing out notes about a text—even if it’s in shorthand—helps you to commit the answers to memory more easily. Even if you don’t write out all these notes, answering these basic questions about any text or reading you encounter in college will help you get the most out of the time you put into your reading. It will also give you more confidence to understand and question the text while you read.

- Is there context provided about the author and/or essay? If so, what stands out as important?

Context in this instance means things like dates of publication, where the piece was originally published, and any biographical information about the author. All of that information will be important for developing a critical reading of the piece, so track what’s available as you read.

- If you had to guess, who is the author’s intended audience? Describe them in as much detail as possible.

Sometimes the author will state who the audience is, but sometimes you have to figure it out by context clues, such as those you tracked above. For instance, the audience for a writer on Buzzfeed is very different from the audience for a writer for the Wall Street Journal—and both writers know that, which means they’re more effective at reaching their readers. Learning how to identify your audience is a crucial writing skill for all genres of writing.

- In your own words, what is the question the author is trying to answer in this piece? What seems to have caused them to write in the first place?

In nonfiction writing of the kind we read in Writing 121, writers set out to answer a question. Their thesis/main argument is usually the answer to the question, so sometimes you can “reverse engineer” the question from that. Often, the question is asked in the title of the piece.

- In your own words, what’s the author’s main idea or argument? If you had to distill it down to one or two sentences, what does the author want you, the reader, to agree with?

If you’ve ever had to write a paper for a class, you’re probably familiar with a thesis or main argument. Published writers also have a thesis (or else they don’t get published!), but sometimes it can be tricky to find in a more sophisticated piece of writing. Trying to put the main argument into your own words can help.

- How many examples and types of evidence did the author provide to support the main argument? Which examples/evidence stood out to you as persuasive?

It’s never enough to just make a claim and expect people to believe it—we have to support that claim with evidence. The types of evidence and examples that will be persuasive to readers depends on the audience, though, which is why it’s important to have some idea of your readers and their expectations.

- Did the author raise any points of skepticism (also known as counterarguments)? Can you identify exactly what page or paragraph where the author does this?

As we’ll see later when the writing process, respectfully engaging with points of skepticism and counterarguments builds trust with the reader because it shows that the writer has thought about the issue from multiple perspectives before arriving at the main argument. Raising a counterargument is not enough, though. Pay careful attention to how the writer responds to that counterargument—is it an effective and persuasive response? If not, perhaps the counterargument has more merit for you than the author’s main argument.

- In your own words, how does the essay conclude? What does the author “want” from us, the readers?

A conclusion usually offers a brief summary of the main argument and some kind of “what’s next?” appeal from the writer to the audience. The “what’s next?” appeal can take many forms, but it’s usually a question for readers to ponder, actions the author thinks people should take, or areas related to the main topic that need more investigation or research. When you read the conclusion, ask yourself, “What does the author want from me now that I’ve read their essay?”

Reading Like Writers: Critical Reading

Reading as a Creative Act

“The theory of books is noble. The scholar of the first age received into him the world around; brooded thereon; gave it the new arrangement of his own mind, and uttered it again. It came into him life; it went out from him truth. It came to him short-lived actions; it went out from him immortal thoughts. It came to him business; it went from him poetry. It was dead fact; now, it is quick thought. It can stand, and it can go. It now endures, it now flies, it now inspires. Precisely in proportion to the depth of mind from which it issued, so high does it soar, so long does it sing.” ~Ralph Waldo Emerson, “The American Scholar”

Objectives

- Consider the discourse community when you read and write in your college classes

- Analyze any reading for text and context

- Read like a writer so you can write for your readers

Image: Bookworms are cool! Bookworm icons created by – Flaticon

By the end of this lesson, you’ll be able to apply the concept of discourse community to honing your college-level critical reading skills.

Good writers are good readers, so let’s start there. When you can confidently identify the audience, context, and purpose of a text—position it within its discourse community—you’ll be a stronger, savvier reader.

Strong, savvy readers are more effective writers because they consider their own audience, context, and purpose when they write and communicate, which makes their writing clearer and to the point.

So the goal of this lesson is to help you read like a writer!

The Savvy Reader

Good writers are good readers! And good readers. . .

Image: Man reading a book by Joel Brown on Pixabay

- get to know the author

- get to know the author’s community + audience

- accurately summarize the author’s argument

- look up terms you don’t know

- “listen” respectfully to the author’s point of view

- have a sense of the larger conversation

- think about other issues related to the conversation

- put it in current context

- analyze and assess the author’s reasoning, evidence, and assumptions

Why read critically? While the best way to develop your skills as a writer is to actually practice by writing, practicing critical reading skills is crucial to becoming a better writer. Careful and skilled readers develop a stronger understanding of topics, learn to better anticipate the needs of the audience, and pick up writing “maneuvers” and strategies from professional writing.

Reading Like Writers

How do you read like a writer? When you read like a writer, you are practicing deeper reading comprehension. In order to understand a text, you are reading not just what’s in it but what’s around it, too: text and context.

|

TEXT |

CONTEXT |

|---|---|

|

|

Practice: Reading Like Writers

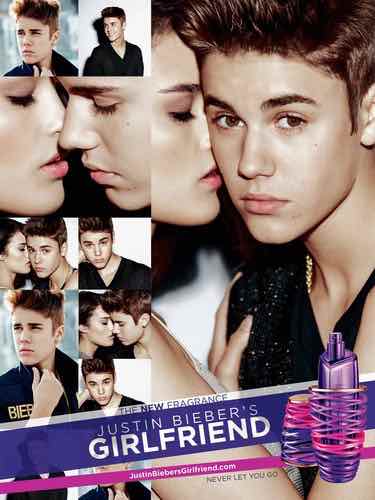

In-class discussion: Advertisements are helpful for practicing reading like writers because advertisers make deliberate choices with text and images based on audience (target consumer), context (where they are reaching them), and purpose (buy this product).

- How does this text—print ad—consider audience, context, and purpose?

- Whom does it appeal to and how does it appeal to them?

- What assumptions or stereotypes does the ad rely on the viewer sharing?

-

- Do you know who Colin Kaepernick is?

- What is the “sacrifice” that’s referred to here?

- How do you interpret Kaepernick’s facial expression?

- Why do you think the advertisers chose a close-up portrait?

- Why use this image and messaging to sell Nike products?

- Whom would this ad appeal to?

- But I’m not trying to sell a product! How can I use my newfound understanding of audience, context, and purpose to improve my writing?

It’s true! You aren’t selling a product. You aren’t (I hope) trying to manipulate your audience. You aren’t relying on discriminatory assumptions or stereotypes to appeal to your audience. But when you write, let’s say, an essay, you are asking readers to “buy into” your point of view. The goal doesn’t have to be for them to agree with you; it can be for your readers to respectfully consider, understand, or sympathize with your point of view or analysis of an issue. The point is you’re thinking of your reader when you write, and that will make your writing process smoother and your writing clearer.

Writing for Your Readers

When you write for your readers, you. . .

- Learn from your reading and communication experience: What makes texts work? How are ideas conveyed clearly?

- Analyze the writing situation: What are the goals and purpose for a writing project? Who is your audience?

- Explore and play as you draft: What are different ways to respond? Can you use a better word or phrase?

- Consider your audience: What might a reader expect to see? What does your reader need to understand your point of view? What questions might a reader have?

Image: Ask more questions; by Jonathan Simcoe , CC0

Writing as a process of inquiry

Just as you want your readers to take you seriously, you want to approach texts with an open and curious mind. Whatever the topic, it was important enough for this person to want to write on it. While we don’t have to agree with the point someone is making, we can respect their opinion and appreciate reading a different perspective.

Approach reading and writing in college in a learning zone. Be open, be curious, ask questions, seek answers. Share, stretch, experiment.

Guides and Worksheets

- Critical Reading Guide [word document] (download here and view below)

- Use this guide for any of your college reading!

- Mark-up Assignment [word document] (download here and view below)

- Learn a basic study skill–annotating or taking notes on your readings

Critical Reading Guide: Text + Context

Title of the text: Author:

Reading the text: Comprehension

Main idea. In one sentence, summarize the main point or argument of the text.

Claim. Identify one claim in the text.

Key points. Paraphrase a key point, example, or passage that interested you.

Evidence. In your own words, describe 1-2 compelling examples or pieces of evidence that support the point/argument of the text.

Conclusion. What is the ultimate takeaway the text gives us on the topic/issue?

Personal experience. What is your experience of the topic? Have you had problems related to it?

Vocabulary. What is a word or phrase in the text you didn’t know? Look it up. What does it mean?

Inquiry. What is one thing you need more information about? Or, what is one question you have about the content of the text?

Reading for context: Rhetorical analysis

The author. Do an internet search on the author. What did you find out?

Ethos. Do you trust the author on the topic/issue? Why or why not?

Container. When and where was the text first published? Who will read/see it?

Audience. How does the author address or appeal to their readers? What tone does the author use in the text?

Bias. What knowledge, values, or beliefs does the author assume the reader shares?

Types of evidence. What types of evidence does the author use? Types of evidence include facts, examples, statistics, statements by authorities (references to or quotes from other sources), interviews, observations, logical reasoning, and personal experience

Structure. How does the author organize the text?

Purpose. What question does the author seek to answer in the text? In other words, why do you think they wrote this piece?

Mark-up Assignment: The Savvy Reader Practice

Purpose

The object is to fill the empty space of the margins with your thoughts and questions to the text. By reading sympathetically (reading to understand what the writer is saying) and critically (reading to analyze and critique what the writer is saying), you are reading mindfully and creatively. You are finding those passages that you are drawn to, asking questions that you have, and beginning to develop your reaction, response, and ideas about a topic or issue. It’s a useful tool in the “getting started” phase of the writing process. Learning how to read effectively will be an invaluable skill in your college career and beyond because it means engaging in a task actively rather than passively.

Task

Choose 1-2 paragraphs from READING X to fully annotate. This passage should be one that interests you, i.e. seems important, confusing, and/or prompted agreement, disagreement, or questions for you.

- Circle any word you think is crucial for the passage, including ones you cannot easily define.

- Underline phrases or images you think crucial for the meaning of the passage/essay.

- Put a bracket around ideas or assertions you find puzzling or questionable.

- Then write notes around the margins of the passage defining these terms, identifying the important ideas, or raising questions with the bracketed phrases. For each item you have circled, underlined, or bracketed, there should be a margin note. For this assignment, your margin notes should be substantive: they should meaty statements and full questions.

Format

Photocopy or clear, legible photograph of paragraphs with your annotations or type up the paragraphs and annotate.